Tea and Jesuits I

The birth of the Jesuit mission in Asia was intimately linked to the Lisbon royal court and Portuguese ambitions for empire. In the first voyage to the East Indies, Portugal sent a small fleet under the command of Vasco da Gama.

His forces landed in India at Calicut, “the City of Spices” in 1498, marking a harsh and persistent Portuguese presence along the west coast of the subcontinent that lasted for centuries. Defeating the Bijapur sultanate and capturing Goa in 1510, conquistadors established the port city as the administrative seat of Portuguese India; explorers then ventured to Malacca, the Spice Islands, and China, where the Portuguese acquired the island port of Macao.

Goa was the headquarters of the Portuguese eastern empire during the reign of King João III the Pious. At the same time, Ignacio de Loyola established the Society of Jesús, becoming its Superior General in 1540 by papal decree. In 1541, the fervent military and mercantile campaigns in the East inflamed the religious zeal of João III who then sent the Jesuit Francis Xavier to the Indies.

Xavier was co-founder of the Society and the first of his order posted as Apostolic Nuncio, Rome’s ambassador to the Indies. Arriving in Goa in 1542, he made the city the center of the Society’s Asian operations, the Jesuits taking up the lead of evangelical Christian missions in the Portuguese Indies. His letters to Ignacio de Loyola in Rome were widely circulated and had the distinction of being the first letters from the East to be published in Europe.[1] After preaching in India and Malacca for many years, Xavier reached Japan. He arrived in the ancient capital of Kyoto in 1549, a mere six years after the Portuguese made landfall in the archipelago. From then on for nearly a century, the Jesuit mission reported from Japan to Rome on its extensive activities in the islands.

The Society recorded in remarkable detail the customs of the Japanese, including the aesthetic practice of hot water and tea, chanoyu 茶の湯. In 1547, the first tentative description of tea was reported to Xavier by his friend Jorge Álvares, the Portuguese sea captain who noted Japanese food and beverages, and obliquely referred to the use of the leaf:

“They drink arrack made from rice; there is also another drink which both the nobles and the people take…In the summer they drink barley water and in winter water mixed with herbs, although I never learnt what these herbs were. Neither in the winter nor in the summer do they drink cold water.”[2]

In time, the ubiquitous drinking of tea was observed to be rather more than just a habit and a beverage. As noted by the Florintine merchant Frencesco Carletti, tea was a social custom that spoke of courtesy and gentility:

“The custom of drinking this cha is so general and widespread among Japanese, that it is almost impossible even to enter anyone’s house without its being offered in a friendly way as a matter of politeness, as they are accustomed to honor their guest in this way…”[3]

Continued in Tea and Jesuits II

Figures

1.

Charles Édouard Armand-Dumaresq (French, 1826 – 1895)

Portrait of Vasco da Gama (1469-1524)

Engraving: ink on paper

Bibliothèque Nationale

Paris, France

2.

Anthonis Mor (Dutch, 1519-1575)

Portrait of King João III of Portugal (reign 1521-1557), ca. 1550

Oil on canvas

Fundación Lázaro Galdiano

Madrid, Spain

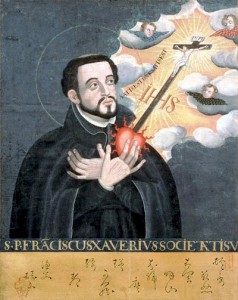

3.

Mancio João Thadeu (1568-1627), attributed

Japan: Edo period, 1615-1886

Portrait of Francis Xavier (1506-1552), ca. 1605-1606

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Kobe Municipal Museum of Namban Art

Kobe, Japan

4.

Chanoyu: tea powder, bowl, and whisk

Notes

[1] Donald Lach, “The Jesuit Letters, Letterbooks, and General Histories,” Asia in the Making of Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965), vol. 1, bk. 1, pp. 315-316.

[2] Michael Cooper, ed., They came to Japan; an anthology of European reports on Japan, 1543-1640 (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1965), p. 191.

[3] Francesco Carletti (Italian, 1573-1636), “La Partenza dall’isole Filippine a quelle del Giappone” (The Departure from the Philippine Islands to those of Japan), Ragionamenti del mio viaggio intorno al mondo [1594-1606] (Discourses on My Journey Around the World) published as Ragionamenti di Francesco Carletti Fiorentino (Discourses of Francesco Carletti the Florentine) (Florence: Stamperioa di Giuseppe Manni, 1701), Discourse 1, pp. 13-14 and Discourse 2, pp. 185 and Michael Cooper, S.J., They Came to Japan: An Anthology of European Reports on Japan, 1543-1640 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1965), p. 199. A similar custom was noted in China. In 1560, Franciscan and Dominican members of mendicant Catholic orders were also in Asia, rivaling the Jesuits in seeking converts and bearing witness to Chinese and Japanese civilizations. The Black Friar Gaspar da Cruz described the Chinese welcoming reception of a worthy guest: “Whatsoever person or persons come to any man’s house of quality, hee hath a custome of offering him…a kind of drinke called ch’a, which is somewhat bitter, red, and medicinall, which they are wont to make with a certayn concoction of herbes” (Gaspar da Cruz, O.P. (Portuguese, circa 1620-1670), Tratado da China (1569); see South China in the sixteenth century: being the narratives of Galeote Pereira, Fr. Gaspar da Cruz, O.P., Fr. Martín de Rada, O.E.S.A. (1550-1575) (London : Printed for the Hakluyt Society, 1953), pp. 140 and 214; and Aniceto dos Reis Gonçalves Viana (Portuguese, 1840-1914), Apostilas aos Dicionários Portugueses (Lisbon, 1906), vol. I, pp. 272-275).