The Abolition of Caked Tea by Imperial Decree

The Veritable Records of Emperor Taizu of the Great Ming Dynasty

Sixteenth day, ninth lunar month, twenty-fourth year [1391] of the Hongwu reign period

An Imperial Decree on the Jianning Annual Offering of Tribute Tea

Obey: the officials of the tea households are ordered to cease harvesting and presenting caked tea. Of all the empire’s tea producers of annual tribute on fixed quotas, the tea of Jianning is supreme. To produce tribute tea, leaves must be crushed and kneaded into pulp and pressed into silver molds to make large and small dragon rounds, a method that greatly strains the resources of the people. Abolish the production of dragon rounds. Pick only tea buds to present as tribute. There are four kinds: Seeking Springtime; Gathering Springtime; Staying Spring; and Russet Shoots. We established five hundred tea households, exempted them from corvée labor, and allowed them to specialize in planting and harvesting tea. Afterwards, there were officials who feared these later reforms and sent overseers to abuse the householders, who dreaded their tyranny. Everywhere bribes were taken. This was reported to the imperial court. Thus, the emperor issues this command.

大明太祖高皇帝實錄

洪武二十四年九月庚子

詔建寧歲貢上供茶 聽茶戶採進 有司勿與 天下產茶去處歲貢皆有定額 而建寧茶品為上 其所進者必碾而揉之 壓以銀板 大小龍團 上以重勞民力 罷造龍團 惟採茶芽以進其品有四 曰探春 屯春 次春 紫筍 置茶戶五百 免其徭役 俾專事採植 既而有司恐其後時 常遣人督之 茶戶畏其逼迫 往往納賂 上聞之 故有是命

Source

DaMing Taizu gao huangdi shilu 大明太祖高皇帝實錄 (The Veritable Records of Emperor Taizu of the Great Ming Dynasty) 卷之二百十二 (Chapter 212).

Figure

Portrait of Emperor Ming Taizu

Ming dynasty

Album leaf: ink, color, and gold on silk

National Palace Museum, Taibei

Moon Festival

Su Shi of the Song dynasty

Poem

Based on the Song of Water Tunes

Moon Festival, 1076

Happily drinking through the night till morning: Truly drunk, wrote this verse, begging the pardon of younger brother, Ziyou.

When will the bright moon appear?

I raise my wine to query the dark sky,

Wondering what year upon palatial Heaven this night falls.

I wish to return there, immortal on the wind,

But I fear I could not bear the cold heights beneath the jade eaves of its jeweled halls.

Rising to dance in joy with my fine moon-shadow,

There is nothing comparable in all the world.

Moonlight eddies about cinnabar pavilions,

Slips beneath latticed doors,

Shining upon the sleepless.

I should have no regrets,

But as we are apart so long, why then is the moon so round?

We all have joy and sorrow, partings and reunions:

The moon waxes and wanes in shadow and light.

Since ancient times, nothing has ever been perfect.

Long may we live,

Though miles apart, and together enjoy the beauty of the moon!

宋 蘇軾

水調歌頭 丙辰中秋,歡飲達旦,大醉。作此篇,兼懷子由

明月幾時有

把酒問青天

不知天上宮闕

今夕是何年

我欲乘風歸去

又恐瓊樓玉宇

高處不勝寒

起舞弄清影

何似在人間

轉朱閣

低綺戶

照無眠

不應有恨

何事長向別時圓

人有悲歡離合

月有陰晴圓缺

此事古難全

但願人長久

千裡共嬋娟

Guanyin Spring at Tiger Hill

Shen Zhou of the Ming dynasty

Sitting beneath pines quietly sipping tea brewed with water drawn from the Third Spring at Tiger Hill under a waning moon

In the evening, I enquire at the monk’s room where to look for a fine mountain stream.

His attendant guides me to a poor village vendor:

This brewing method is not in keeping with Master Lu’s tea.

Firstly, take and light the bamboo tallies of Master Su.

The stone tripod boils, the draft rousing fine green waves.

See how the porcelain cup holds the moon like a golden bauble!

Beneath the long pines, sips fill with soft songs.

Without poetry, the flavor only withers.

明 沈周

月夕汲虎丘第三泉煑茶坐松下清啜

夜扣僧房覔磵腴

山童道我吝村沽

未傳盧氏煎茶法

先執蘇公調水符

石鼎沸風憐碧縐

磁甌盛月看金鋪

細吟滿啜長松下

若使無詩味亦枯

Source

Shen Zhou 沈周 (1427-1509), “Yüexi ji Huqiu Disanqüan zhucha zuo songxia qingchuai

月夕汲虎丘第三泉煑茶坐松下清啜 (Sitting beneath pines quietly sipping tea brewed with water drawn from the Third Spring at Tiger Hill [in the eighth lunar month] under a waning moon),” Shitian shixüan 石田詩選, ch. 2 in Chen Binfan 陳彬藩 and Yü Yüe 余悅, eds., Zhongguo cha wenhua jingdian 中國茶文化經典 (Beijing: Guangming ribao chuban she, 1999), p. 408.

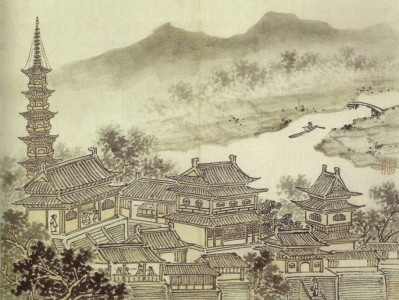

Figure

Shen Zhou (1427-1509)

Twelve Views of Tiger Hill : The Thousand Buddha Hall and the Pagoda of the Cloudy Cliff Monastery

Leaf seven from an album of twelve leaves

Ink and color on paper

The Cleveland Museum of Art

Paradox

Laozi of the Zhou dynasty

Books of the Path and the Power

Paradox

Profound accomplishment appears unaccomplished, yet it is ever present and infinite.

Utter completeness appears incomplete, yet it is ever present and limitless.

True virtue appears as vice.

True art appears artless.

True expression appears inarticulate.

Stillness transcends restlessness, detachment transcends attachment.

Clarity and serenity rectify the world.

悖論

大成若缺其用不弊

大盈若沖其用不窮

大直若屈

大巧若拙

大辯若訥

靜勝躁寒勝熱

清靜為天下正

Source

Laozi 老子, [Beilun 悖論 (Paradox)], Daode jing 道德經 (Books of the Path and the Power in 2 parts.; emended from various sources, huijiaoban 匯校版), part 2, ch. 45.

Figure

Zhao Buzhi 晁補之 (1053-1110 A.D.)

Laozi qi’niu tu 老子騎牛圖 (Laozi Riding an Ox)

China: Song dynasty

Hanging scroll: ink on paper

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Republic of China

Hymn to Tea

Wuzhu of the Tang dynasty

Hymn to Tea

Deep, secluded valleys bear forth the divine herb:

The luminous means to Enter the Way.

Gatherers picking leaves;

Delicate flavors flowing into bowls.

Peace and purity realized,

The Enlightened Mind reveals levels of Awareness.

Effortlessly, without attachment or toil,

The soaring Dharma Gate opens.

唐 無住

茶偈

幽谷生靈草

堪為入道媒

樵人採其葉

美味入流杯

靜虛澄虛識

明心照會臺

不勞人氣力

直聳法門開

Source

Wuzhu 無住 (714-774 A.D.), Chaji 茶偈 (Hymn to Tea), Lidai fabao ji 曆代法寶記 (Record of the Dharma Treasure through the Generations) in Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎, (1866-1945 A.D.) et al., eds., Taishō shinshū Daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (a.k.a. Dazheng xinxiu dazangjing, Taisho Tripitaka, 100 vols.) (Tokyo: Taisho Issaikyo Kankokai, 1924-1934), ch. 51, no. 2075, p. 193b.

A Song of Drinking Tea on the Departure of Zheng Rong

Dedicated to Sylvia and Matthew London for their friendship and generosity

Jiaoran of the Tang dynasty

A Song of Drinking Tea on the Departure of Zheng Rong

The immortal Danqiu abandoned eating jade elixirs,

Picking tea instead, he drank, and grew feathered wings.

The world is unaware of the Mansion of Eminent and Hidden Immortals,

People do not know of the Palace of Transmuting Bone into Clouds.

The Lad of Cloudy Mountain blended it in a gold cauldron;

How hollow the fame of the Man of Chu and his Book of Tea!

Late on a frosty night, breaking cakes of fragrant tea.

Brewed to overflowing, the pale yellow froth; I sip and am reborn.

Bestowed by the gentleman, this tea dispels my suffering,

Cleansing my mind from worry and fear.

Come morning, the emotions of the fragrant brazier remain.

Intoxicated still, we walk across the clouds reflected in Tiger Stream;

In high song, I send the gentleman off.

唐 晈然

飲茶歌送鄭容

丹丘羽人輕玉食

採茶飲之生羽翼

名藏仙府世空知

骨化雲宮人不識

雲山童子調金鐺

楚人茶經虛得名

霜天半夜芳草折

爛漫緗花啜又生

賞君此茶祛我疾

使人胸中蕩憂栗

日上香爐情未畢

醉踏虎溪雲

高歌送君出

Note

For this and other Chinese tea poems, see the forthcoming

THE SPIRIT OF TEA: An Offering To Tea Lovers

a book of photography by Matthew London

Tiger Spring Press, 2014

or go to www.spiritoftea.org

Source

Jiaoran 晈然 (730-799 A.D.), “Yincha ge sung Zheng Rong 飲茶歌送鄭容 (A Song of Drinking Tea on the Departure of Zheng Rong) in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Qüan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 821, no. 13.

Happy that Tea Grows in the Garden

Dedicated to Sylvia and Matthew London for their friendship and generosity

Wei Yingwu of the Tang dynasty

Happy that Tea Grows in the Garden

Its purity cannot be stained.

Drinking it washes away dust and despair.

This earthly thing truly has an unearthly allure.

My tree is originally from its home in the mountains.

Taking a bit of time from prefectural duties,

I hastily planted it in my tangled garden.

Happily, it thrived full and tall, and now through tea,

I commune with the mystic spirits.

唐 韋應物

喜園中茶生

潔性不可污

爲飲滌塵煩

此物信靈味

本自出山原

聊因理郡餘

率爾植荒園

喜隨衆草長

得與幽人言

Note

For this and other Chinese tea poems, see the forthcoming

THE SPIRIT OF TEA: An Offering To Tea Lovers

a book of photography by Matthew London

Tiger Spring Press, 2014

or go to www.spiritoftea.org

Source

Wei Yingwu 韋應物 (737-792 A.D.), “Xi yüanzhong chasheng 喜園中茶生 (Happy that Tea Grows in the Garden)” in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Qüan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 193, no. 55.

Tea: A Pagoda Poem

Dedicated to Sylvia and Matthew London for their friendship and generosity

Yüan Zhen of the Tang dynasty

Tea: A Pagoda Poem

Tea

Fragrant leaves, tender buds

The desire of poets, the love of monks

Ground in carved white jade, sifted through red gauze

Cauldron brewed to the color of gold, bowl aswirl in floral foam

At night it welcomes the bright moon, at daybreak it dispels dawn’s rosy mists

Past and present, drinkers are refreshed and tireless, praisefully aware it quells drunkenness

唐 元稹

茶寶塔詩

茶

香葉嫩芽

慕詩客愛僧家

碾雕白玉羅織紅紗

銚煎黃蕊色碗轉曲塵花

夜後邀陪明月晨前命對朝霞

洗盡古今人不倦將知醉後豈堪誇

Note

For this and other Chinese tea poems, see the forthcoming

THE SPIRIT OF TEA: An Offering To Tea Lovers

a book of photography by Matthew London

Tiger Spring Press, 2014

or go to www.spiritoftea.org

Source

Yüan Zhen 元稹 (799-831 A.D.), “Cha 茶 (Tea)” in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Qüan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 423, no. 24.

Figure

Reconstruction Drawing of the Yongning Temple Pagoda at Luoyang 洛陽永寧寺塔圖

Originally built in 516 A.D. during the Northern Wei Dynasty

Wandering Immortal

Guo Pu of the Eastern Jin

Poem Nine of Nineteen Poems on Wandering Immortal

Picking herbs, roaming the great mountains:

I deter the decay of old age.

Nurturing breath and liquid jade:

A marvelous spirit fills the breast.

Becoming immortal, I steady the dragon steeds,

Driving hard the thundering chariot.

Scales send forth bright lightning,

Canopied clouds trail swirling winds.

Reining in the traces of the Sun chariot,

I stamp my foot to open Heaven’s Gate.

The Eastern Sea is like a puddle in a hoof print,

Mount Kunlun, an anthill.

So vast and boundless the Void,

To behold the abyss makes one despair.

東晉 郭璞

郭璞全集

游仙詩十九首

第九

採藥游名山

將以救年頹

呼吸玉滋液

妙氣盈胸懷

登仙撫龍駟

迅駕乘奔雷

鱗裳逐電曜

雲蓋隨風回

手頓羲和轡

足蹈閶闔開

東海猶蹄涔

昆侖螻蟻堆

遐邈冥茫中

俯視令人哀

Sources

閔福德 和 劉紹銘, 主編 (John Minford and Joseph S.M. Lau, comps.), 含英咀華 上卷: 遠古時代至唐代 (A Chinese Companion to Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations) (Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2001), p. 164. Cf. Graeme Wilson, trans., “Vision: Second Poem of Wandering Immortals,” An Anthology of Translations: Classical Chinese Literature, Volume I: From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty, John Minford and Joseph S.M. Lau, comps. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), p. 438.

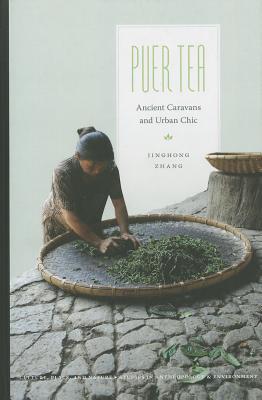

Puer Tea: Ancient Caravans and Urban Chic

Puer Tea is a study of the tea industry in the distant southwest province of Yünnan. The book traces the path of the Chinese tea known as Pu’er from the remote villages along the Tea Horse Road to the elegant salons of China’s cosmopolitan centers. Author Jinghong Zhang presents her report as a “cultural biography” and centers on the tea business during the decade 1997-2007 when Pu’er tea was a commercial and culinary phenomenon that swept the tea drinking world. She takes a penetrating look at Pu’er tea through the lens of the anthropologist, a perspective sharply focused on the varied spheres of tea, from cultivator to connoisseur.

Puer Tea is a study of the tea industry in the distant southwest province of Yünnan. The book traces the path of the Chinese tea known as Pu’er from the remote villages along the Tea Horse Road to the elegant salons of China’s cosmopolitan centers. Author Jinghong Zhang presents her report as a “cultural biography” and centers on the tea business during the decade 1997-2007 when Pu’er tea was a commercial and culinary phenomenon that swept the tea drinking world. She takes a penetrating look at Pu’er tea through the lens of the anthropologist, a perspective sharply focused on the varied spheres of tea, from cultivator to connoisseur.

In the wide realm of tea books, Puer Tea is unusual if not unique in its exploration of the complex social relationships that permeate the tea trade, the intricate yet often opaque bonds that ultimately determine the character and quality of the tea we drink.

Zhang delves into the story of Pu’er tea by simply unfolding village farm life in deeply rural Yünnan. In the process, she artlessly reveals the convoluted social, ethnic, and cultural effects wrought by the sudden interest in a local product, a distinctive artisanal tea that is universally celebrated as Pu’er. Riven by demand, government regulation, hyperbole, and greed, what had been a supplemental cottage craft changed within a decade into a big business industry with both predictable risks and unexpected consequences. Zhang documents the processes by which villagers responded to outside forces like the media and government regulation and she explores the motivating logic of their behavior. Moving from producers to traders, she notes the complaints of tea buyers about the difficulties in finding quality leaf and observes the perils of their business when competition and market dynamics undermine the very relations on which their trade depends. She follows Pu’er tea from the countryside to the city where scientists and scholars are viewed with suspicion and defiance by traders, connoisseurs, and collectors.

Zhang took her inaugural journey into the heart of Pu’er tea in 2002 when she visited the secluded village of Yiwu in Xishuangbanna prefecture. The outside world was beginning to find its way through the back country roads and trails up into the subtropical forests alive with tea. Returning in March 2007, she became aware of changes among the inhabitants but could not have foreseen the events that would adversely affect them in the months to come. Seeking strength in numbers, the villagers formed the Yiwu Authentic Tea Mountain Company, Ltd. in response to government taxation and regulation. Meanwhile the provincial government implemented the Quality Safety Standards during an abnormally dry winter and spring season that severely limited the amount of premium leaves picked from the field. There was a dramatic rise in the price of processed leaves due to limited supply of quality leaf and cut throat competition, followed by a subsequent rise in production costs owing to price hikes and uncertainty of the tea supply. The newly christened city of Pu’er experienced an earthquake on June 3rd that presaged the collapse of the Pu’er tea market and the beginnings of a steep trade decline that was further damaged by the worldwide recession of 2008. In her study, Zhang provides an eyewitness account of a particularly crucial moment of upheaval in the Pu’er tea trade.

Zhang addresses the remarkable diversity and subtlety of standpoints on Pu’er tea from a position of considerable knowledge. Trained in China and Australia, she is expert in field anthropology and skilled in employing the range of requisite anthropological theories, methods and techniques, including video, photography, graphs, and maps. Furthermore, Zhang is from Yünnan and is intimately familiar with the dialectical languages of the province, local and regional values and traditions as well as the historical racial, ethnic, and religious sensitivities of the people. Dr. Jinghong Zhang is a lecturer at Yünnan University and a post doctoral fellow at the Australian National University.

In the eight chapters of Puer Tea, Zhang follows a scenario of rise, climax, and denouement in which Pu’er is initially framed as the single most important activity around which the economic life of one village in remote China is organized. Then the narrative shifts, and peasant interests in the tea harvest, processing, and production give way to the concerns of the urban trader to supply the growing Asian and global markets with fine Pu’er tea. Intent on preserving traditional methods and making an authentic and organic tea from wild and arbor stock, producer and merchant contend with government efforts to regulate production. State efforts to standardize and establish quality control not only result in mechanization and industrialization but also undercut authenticity and quality. Media interest and promotional hyperbole fuel annual inflation at every level – material, production, wholesale, and retail – until confidence falls and the market collapses.

Inspired by the traditional Chinese literary theme and agrarian motif of the four seasons, the author depicts the dramatic rise and fall of Pu’er tea as the promise of spring, the fulfillment of summer, the autumnal harvest, and the harshness of winter. She also employs other traditional ideals such as health, wealth and prosperity, frugality and simplicity, the return to the ancient, and the related compounded notion of the natural, the original, and the authentic.

Of all the Chinese notions, Zhang most deftly uses the concept of Jianghu to describe the chaos of the Pu’er industry. Jianghu is a historical and literary phrase meaning the “rivers and lakes” that described the aquatic landscape of the great region south of the Yangzi. In antiquity, the majestic river marked the boundary between the well ordered north and the anarchic south, between civilization and savagery. In ancient poetry and literature, Jianghu evoked not only an exotic land vibrant with color, texture, and spice but also an alien place of miasmic heat and humidity, barbarity, and the stigma of exile and death. Those who survived Jianghu became Jianghu and converts to a sub rosa culture that thrived on the uncertainties of life. As she writes throughout Puer Tea, the various persons in the book personify characters enacting different roles in a drama set in the turbulent world of Jianghu and tea.

While demonstrating a command of anthropological interests and fulfilling its requisites, Dr. Zhang presents Pu’er tea in a clear and colloquial manner that is easily understood by the lay reader. Her objective view inside the Pu’er industry is a welcome take, especially since the debacle in 2007 and given the opacity of the trade. Filled with insight and revelation, Zhang engagingly provides the reader an extraordinary glimpse into the riotous theater of Pu’er tea.

Jinghong Zhang

Puer Tea: Ancient Caravans and Urban Chic

University of Washington Press

2013

A Visit to Teance

Teance is the premier tea room in the San Francisco Bay Area. No other such place offers tea in either so thoughtful a manner or in so creative a space. The shop is nestled on a terrace above a quiet lane in the bustling 4th Street district of Berkeley. The wide awning and fully windowed front greet and open in welcome. On traversing the mosaic threshold, the very considered character of Teance is immediately apparent and directly appealing.

Once within, there is a momentary feeling of ascension. The eye soars to the high ceiling – brightened by skylight and an immense hanging lantern ablaze in orange red – only to drop precipitously to the ink black floor, a dark elaborate board of ceramic and stone tiles, each giving depth and mass to the fleeting instance of transcendence. Entering Teance gives the distinct sense of crossing into a world beyond.

The essential elements are everywhere. A garden pond invites with long stemmed aquatic plants and flashes of intense color as goldfish swim amidst the dark recesses of the pool. Water cascades gently from above into a mossy basin, pitter-pattering in asymmetric syncopation on stone, the shower ionically charging and freshening the air and filling the pond below. Follow the long weighty column of calcified basalt to the color muted interior, a smooth pale ground set sparingly with polychrome flecks of stone.

From the floor rises the exquisite tea bar. Cast in a single pour of fine concrete inlaid with stone, shell, and minerals, the counter inset with drain stations of pure copper, mottled and stained, on which to brew tea. Bearing a rich patina from use, the bar is unique, a mirror of the pond: forms of earth and water embodying the open ensō, the Zen circle of enlightenment and spiritual perfection.

Winnie Yu is Director of Teance and curator of the seasonal selection of teas from China, Korea, Japan, and India. Petite and gracious, she radiates a calm certainty from within the tea bar as she prepares and serves a succession of light to dark premium teas:

Anhui Yellow – a yellow tea from Mount Jin Zai, Anhui

Gyokuro – a green tea from Uji, Japan

Four Seasons – a wulong tea from Nantou, Taiwan

Phoenix Honey Fragrance – a wulong tea from Phoenix

Mountain, Guangdong

Yunnan Gold – a black tea from Yunnan

The simplicity of her casual gestures belies the masterful techniques by which she brews each tea. Frugality, economy, and practicality transform her motions into an elegant ballet. From one cup to another, the subtle rhythms of the leaf enfold as if notes on a score, lightly played yet resonant and deepened with every steep. She pours clear water into the gaiwan, then spreads green gyokuro in a circular motion into the cup. The tea floats a bit, as if surprised, and then rapidly sinks to provide a brew redolent with umami, the intense and savory taste – the pursuit and delight of the connoisseur.

The simplicity of her casual gestures belies the masterful techniques by which she brews each tea. Frugality, economy, and practicality transform her motions into an elegant ballet. From one cup to another, the subtle rhythms of the leaf enfold as if notes on a score, lightly played yet resonant and deepened with every steep. She pours clear water into the gaiwan, then spreads green gyokuro in a circular motion into the cup. The tea floats a bit, as if surprised, and then rapidly sinks to provide a brew redolent with umami, the intense and savory taste – the pursuit and delight of the connoisseur.

Yu hails from Hong Kong, where at the age of four she learned to drink tea. Her mother is the scholar Yuen Chuen Tam and her father, the renowned painter Chitfu Yu, who in 1978 moved the family from China to New York and presently resides in New Jersey.

Winnie graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, a city by the Bay where she stayed and prospers. Adhering to literati traditions, she melds the ancient and the new within the store: Yu translates old Chinese tea poems for her patrons, giving recitations and lectures; her father’s calligraphy graces its walls, his ink paintings filling the unexpected places. And Winnie Yu’s innate sense of the good and proper permeates the Teance experience. A revelation and a pleasure not to be missed.

Former Address and Numbers

Teance

1780 4th Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

510-524-2832

www.teance.com

Current Address and Numbers

Teance Fine Teas

In the Heart of South by Southwest Berkeley

1036 Grayson Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

Tel: 510-524-1696

Email:info@teance.com

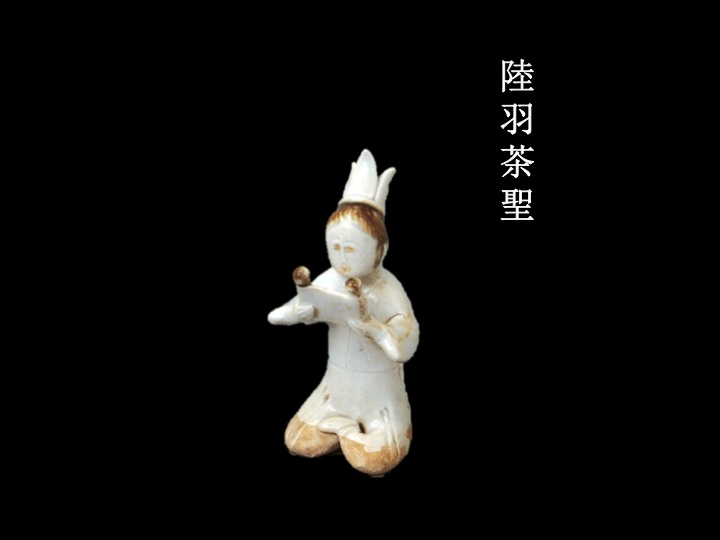

Biographies of Lu Yü: Translations and Texts

Transmitted Records of the Great Tang Dynasty

Author unknown, 9th century C.E.

Number twenty-four

Lu Hongjian was fond of tea. He wrote the Book of Tea in three volumes; the book was popular in its time. It was common for the tea guilds to commission pottery kilns to make porcelain figures of him to set upon the brazier and cauldron to exert his influence as the God of Tea. During business, either leaf tea was offered to the figure or brewed tea was used to pour over it.

大唐傳載

不著撰人名氏, 第九世纪公元

第二十四

陸鴻漸嗜茶,撰《茶經》三卷,行於代。常見鬻茶邸燒瓦瓷為其形貌,置於竈釜上,左右為茶神。有交易則茶祭之,無則以釜湯沃之。

Li Zhao (flourished circa 818-821 C.E.)

Supplement to the Dynastic History of the Tang

Chapter two

“Lu Yü takes a surname and a given name”

A Buddhist monk from Jingling discovered a foundling boy on a riverbank and raised him as his disciple. When he was a little older, the boy divined the Book of Changes and received the hexagram jian 漸 from the hexagram jian 蹇 and the oracular words: “Hong jianyü lu, qi yü keyong wei yi, The wild goose gradually draws near land, its feathers can be used for rites.” Thus, he took the surname Lu, the given name Yü, and the sobriquet Hongjian.

Yü possessed erudition and many ideas, and so it was a shame that only one thing completely engaged his genius – namely, spreading the art of tea. The potters of Gong county made many porcelain figures of him, calling them each Lu Hongjian. When someone bought many tens of tea implements from a shop, he got a Hongjian figure. When city tea traders did not make a profit, they then poured tea over it. In the Jianghu region, Yü was called Master Jingling. In the Nanyüe region, he was called Old Man Mulberry. Yü had a close friendship with Yan Lugong and was a friend of Master Xüanzhen, Zhang Zhihe. When he was young, he worked for the Zen master Zhiji. One day, Yü heard that the Zen master had passed away. He wept in deep lament and composed a poem to express his feelings:

“I do not desire cups of white jade

Nor covet wine vessels of yellow gold.

I do not yearn for court matins

Nor long for evening audiences.

I do have a thousand yearnings, ten thousand longings

For the western waters of the River

Flowing just beyond the walls of Jingling.”

Lu Yü died at the end of the Zhenyüan reign period.

李肇撰

唐國史補

卷中

陸羽得姓名(氏)

竟陵僧有於水濱得嬰兒者,育為弟子,稍長,自筮得《蹇》之《漸》繇曰:「鴻漸於陸,其羽可用為儀。」乃令姓陸名羽,字鴻漸。羽有文學,多意思,恥一物不盡 其妙,茶術尤著。鞏縣陶者多為甆偶人,號陸鴻漸,買數十茶器得一鴻漸,市人沽茗不利,輒灌注之。羽於江湖稱「竟陵子」,於南越稱「桑薴翁」。與顏魯公厚 善,及玄真子張志和為友。羽少事竟陵禪師智積,異日在他處聞禪師去世,哭之甚哀,乃作詩寄情,其略云:「不羨白玉盞,不羨黃金罍。亦不羨朝入省,亦不羨暮 入臺。千羨萬羨西江水,曾向竟陵城下來。」貞元末卒。

Zhao Lin (jinshi degree, 834 C.E.)

Stories of Cause and Consequence

Chapter three

Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent Lu Hongjian was named Yü. His ancestry is unknown. A monk from the Longxing Monastery at Jingling, who was surnamed Lu, found a baby boy on an embankment and raised him. Accordingly, he gave his last name Lu to the child. When the boy was grown, he was intelligent, gifted, and accomplished. His erudition was imaginative and his words forceful. In debate, he was witty and articulate. In the evening, he was an expansive and fine companion.

Other narratives of his life include those of Master Cao on the maternal grandfather’s side of the Yü family; the Yang family in-laws; Cao Huitan, whose sobriquet is Zhongyong, on the maternal grandfather’s side of the Hong family. Those friendships were sincere and profound. Maternal grandfather kept a letter composed by Master Lu.

By nature, Lu Yü was fond of tea and introduced the art of tea. To this day, families of the tea guilds commission pottery figures of his likeness and set them among the braziers, saying “That which is felicitous to tea, attains prosperity.”

I still remember knowing, when I was young, an old monk from Fuzhou who was a disciple of Brother Lu. He always chanted

“I do not desire wine vessels of yellow gold

Nor covet cups of white jade.

I do not yearn for court matins

Nor long for evening audiences.

I do have a thousand yearnings, ten thousand longings

For the western waters of the River

Flowing just beyond the walls of Jingling.”

and captured all of the emotion of Brother Lu’s poem.

趙璘撰

因話錄

卷三

太子陸文學鴻漸名羽,其先不知何許人。竟陵龍興寺僧,姓陸,於堤上得一初生兒,收育之,遂以陸為氏。及長,聰俊多能,學贍辭逸,詼諧縱辯,蓋東方曼倩之 儔。與餘外祖戶曹府君,外族柳氏,外祖洪府戶曹諱澹,字中庸,別有傳。交契深至。外祖有牋事狀,陸君所撰。性嗜茶,始創煎茶法,至今鬻茶之家,陶為其像, 置於煬器之間,雲宜茶足利。余幼年尚記識一復州老僧,是陸僧弟子。常諷其歌云:「不羨黃金罍,不羨白玉杯,不羨朝入省,不羨暮入臺。千羨萬羨西江水,曾向 竟陵城下來。」又有追感陸僧詩至多。

Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072 C.E.) and Song Qi (998-1061 C.E.), compilers

New Dynastic History of the Tang, 1060 C.E.

Chapter One hundred ninety-six

Historical Biography, Chapter One hundred twenty-one

Eremites

Lu Yü, whose sobriquet was Hongjian (an alternate given name was Ji and the sobriquet was Jici), a native of Jingling, Fuzhou. His paternity was unknown, but it was said that there was a monk who discovered him on a riverbank and raised him. When he was older, he used the Book of Changes to divine the hexagram jian 漸 from the hexagram jian 蹇 which read: “Hong jianyü lu, qi yü keyong wei yi, The wild goose gradually draws near land, its feathers can be used for rites.” And so, he took Lu as his surname as well as his given name and sobriquet from it.

When he was young, his master taught him Buddhist scripture, to which he responded, “To end relations with one’s brethren and sever posterity, do these fulfill the obligations of filial piety?” His master was furious and made him handle manure to repair the plaster as punishment. He made him herd thirty head of cattle, but Yü secretly used a bamboo stick to practice writing characters on the bovines’ backs. He obtained a copy of “Ode on the Southern Capital” by Zhang Heng, but he could not read it; and so, he knelt repectfully, imitating the file of schoolboys, mumbling as if reading fervently. His master restrained him, ordering him to pull rank weed and grass. Prevented from learning characters, he became befuddled, as if at a loss, insufferably passing each day. His master whipped him, making him moan, “The months and years are passing by; how will I ever survive not knowing writing and books?” Sobbing unbearably, he ran away to hide, becoming an actor and writing several thousand jokes and japes. During the Tianbao reign period, officials of Fuzhou appointed Yü master of entertainments at a banquet. Governor Li Qiwu recognized his talent, rewarding him with books, and recommending him to boarding school at Mount Huomen.

In appearance, he was ugly. He stuttered but was persuasive. Hearing people do good, he felt good. Seeing people oblivious and foul, he admonished the most offensive. When amongst friends but happened to think of something, he withdrew aside and departed, leaving people to wonder if he was angry. When devoted to someone, rain and snow, tigers and wolves could not force him to forsake him. At the beginning of the Shangyüan reign period, he went into seclusion along the Tiaoxi Stream. He called himself Old Man Mulberry and closed his door to write books. Alone in the wilds, he chanted out loud, knocking about the trees, wandering aimlessly, wretched and weeping before returning home. So then, he was known as the modern day Jieyü. After a long time, he received an official post by imperial decree, and Yü became Imperial Instructor of the Heir Apparent and was appointed Great Supplicator at the Court of Imperial Sacrifices. He declined the offices. At the end of the Zhenyüan reign period, he died.

Lu Yü was fond of tea. He authored the Book of Tea in three chapters, explaining the origins of tea, its methods, implements and equipage, and especially its preparation so that All under Heaven knew the virtues and wisdom of drinking tea. At the time, the tea guilds commissioned a ceramic figure of Yü to set among the braizers to offer libations to it as the God of Tea. There once was a Chang Boxiung, who because of Yü’s revelations, zealously extolled the merits of tea. The Censor-in-Chief Li Jiqing made an imperial tour of inspection of Jiangnan and stopped in Linghuai. He knew that Chang Boxiung excelled at brewing tea and so summoned him. Boxiung carried his implements in front of him, and because of this, Jiqing drank two bowls of tea. Upon reaching Jiangnan, someone recommended Yü to him, and so he summoned him. Dressed in rustic clothes, Yü entered ahead of his equipage, and therefore Jiqing regarded him with contempt. Yü blamed him, and in revenge wrote The Ruination of Tea. Later, tea became the fashion, and in time, even the Uighurs entered the capital, driving their horses to market for tea.

歐陽修 宋祁撰

新唐書

卷一百九十六

列傳第一百二十一

隱逸

陸羽,字鴻漸,一名疾,字季疵,複州竟陵人。不知所生,或言有僧得諸水濱,畜之。既長,以《易》自筮,得《蹇》之《漸》,曰:「鴻漸於陸,其羽可用為儀。」乃以陸為氏,名而字之。

幼時,其師教以旁行書,答曰:「終鮮兄弟,而絕後嗣,得為孝乎?」師怒,使執糞除圬塓以苦之,又使牧牛三十,羽潛以竹畫牛背為字。得張衡《南都 賦》,不能讀,危坐效群兒囁嚅若成誦狀,師拘之,令薙草莽。當其記文字,懵懵若有遺,過日不作,主者鞭苦,因歎曰:「歲月往矣,奈何不知書!」嗚咽不自勝,因亡去,匿為優人,作詼諧數千言。

天寶中,州人酺,吏署羽伶師,太守李齊物見,異之,授以書,遂廬火門山。貌侻陋,口吃而辯。聞人善,若在己,見有過者,規切至忤人。朋友燕處,意有 所行輒去,人疑其多嗔。與人期,雨雪虎狼不避也。上元初,更隱苕溪,自稱桑薴翁,闔門著書。或獨行野中,誦詩擊木,裴回不得意,或慟哭而歸,故時謂今接輿 也。久之,詔拜羽太子文學,徙太常寺太祝,不就職。貞元末,卒。

羽嗜茶,著經三篇,言茶之原、之法、之具尤備,天下益知飲茶矣。時鬻茶者,至陶羽形置煬突間,祀為茶神。有常伯熊者,因羽論複廣著茶之功。御史大夫 李季卿宣慰江南,次臨淮,知伯熊善煮茶,召之,伯熊執器前,季卿為再舉杯。至江南,又有薦羽者,召之,羽衣野服,挈具而入,季卿不為禮,羽愧之,更著《毀 茶論》。其後尚茶成風,時回紇入朝,始驅馬市茶。

Xin Wenfang (active circa 1304-1324 C.E.)

Biographies of the Talents of the Tang Dynasty, 1304 C.E.

Chapter three

Lu Yü

Yü, his sobriquet was Hongjian; parentage unknown. Early in life, the Zen master Zhiji discovered the foundling on a riverbank and raised him as his disciple. When he was grown, he was ashamed to take the tonsure, and so using the Book of Changes, he divined the hexagram jian 漸 from the hexagram jian 蹇 which read: “Hong jianyü lu, qi yü keyong wei yi, The wild goose gradually draws near land, its feathers can be used for rites” and began using the characters for his surname and given name.

He was learned, and there was nothing in which he did not excel. By nature, he was witty. When he was young, he hid among theater actors and composed Mocking Banter of a myriad jokes. During the Tianbao reign period, the local bureau appointed him master of entertainments, but he later went into seclusion. In antiquity, people called this “to cleanse oneself of a humble past.” At the beginning of the Shangyüan reign period, he built a hut along Tiaoxi Stream, closing his door to read books and talking and gathering with eminent monks and lofty scholars all day long. In appearance, he was ugly; he stuttered but was eloquent. Hearing people do good, he felt good. Regarding friends, although obstructed by tigers and wolves, he would not desert them.

He called himself Old Man Mulberry and also Master of East Ridge. He was skilled in ancient tunes, songs, and poems, the epitome of elegance. He authored a great many books. He went back and forth by skiff among the mountain temples wearing only a gauze kerchief and straw sandles, a coarse cloth shirt and shorts. He knocked about the forest, dabbling in flowing streams, wandering in the wilderness, reciting ancient poems, unwilling to leave until dark. Filled with grief, he wailed and wept, and finally returned home. At the time, he was compared to Jieyü. He and the Buddhist priest Jiaoran shared a close rapport. He received an official post by imperial decree as Imperial Instructor of the Heir Apparent.

Lu Yü was fond of tea. He created a profound and subtle way and wrote the Book of Tea in three volumes which described the origins, methods, and equipage of tea. In time, he was known as the Immortal of Tea, and All under Heaven benefited from drinking tea. The tea guilds commissioned a ceramic figure of Yü and offered libations to it as a deity. When someone bought ten tea implements from a shop, he got a Hongjian figure.

Early on, the Censor-in-Chief Li Jiqing conducted an imperial tour of inspection in Jiangnan. Liking tea, he knew of Yü, and so he summoned him. Yü, in rustic clothes, entered ahead of his equipage. Li said, “Master Lu excells at tea; All under Heaven knows this. The water from Zhongling on the Yangzi is also exceptional. Now these two marvels have come together in a rare moment of providence. You, honored recluse, must not miss this opportunity.” When the tea was over, Li ordered a servant to give money to Lu Yü. Humiliated, Lu Yü blamed Li Jiqing, and in revenge wrote The Ruination of Tea.

He was a worthy traveling companion of Huangfu Zai. Once, the minister Bao Fang was in Yüe, and Yü went to serve him. Huangfu Zai composed a preface for him, saying “Gentleman Yü studies the philosophies of both Confucius and Buddha, and esteems song and poetry. Be it boating to a distant cottage or a lonely island, he is compelled to roam. Whether weir fishing or angling from a jetty, he goes where he wishes. Yüe is a strategic land of mountains and waters and therefore bears a heavy badge of office. Lord Bao appreciates and admires Master Yü; he shows him the utmost respect. It is a rare treat to taste the fish of Jinghu, much like grasping the reflection of the moon in a stream.” Composed for the Book of Tea to spread its fame.

辛文房

唐才子傳

卷三

陸羽

羽,字鴻漸,不知所生。初,竟陵禪師智積得嬰兒於水濱,育為弟子。及長,恥従削發,以《易》自筮,得《蹇》之《漸》曰:『鴻漸於陸,其羽可用為儀。』始為 姓名。有學,愧一事不盡其妙。性詼諧,少年匿優人中,撰《談笑》萬言。天寶間,署羽伶師,後遁去。古人謂『潔其行而穢其跡『者也。上元初,結廬苕溪上,閉 門讀書。名僧高士,談宴終日。貌寢,口吃而辯。聞人善,若在己。與人期,雖阻虎狼不避也。自稱『桑薴翁』,又號『東崗子』。工古調歌詩,興極閑雅。著書甚 多。扁舟往來山寺,唯紗巾藤鞋,短褐犢鼻,擊林木,弄流水。或行曠野中,誦古詩,裴回至月黑,興盡慟哭而返。當時以比接輿也。與皎然上人為忘言之交。有詔 拜太子文學。羽嗜茶,造妙理,著《茶經》三卷,言茶之原、之法、之具,時號『茶仙』,天下益知飲茶矣。鬻茶家以瓷陶羽形,祀為神,買十茶器,得一鴻漸。 初,禦史大夫李季卿宣慰江南,喜茶,知羽,召之。羽野服絜具而入,李曰:『陸君善茶,天下所知。揚子中泠水,又殊絕。今二妙千載一遇,山人不可輕失也。』 茶畢,命奴子與錢。羽愧之,更著《毀茶論》。與皇甫補闕善。時鮑尚書防在越,羽往依焉,冉送以序曰:『君子究孔、釋之名理,窮歌詩之麗則。遠野孤島,通舟 必行;魚梁鉤磯,隨意而往。夫越地稱山水之鄉,轅門當節鉞之重。鮑侯知子愛子者,將解衣推食,豈徒嘗鏡水之魚,宿耶溪之月而已。』集並《茶經》今傳.

Tianmen County Annals of the Qianlong Reign Period

Chapter Seventeen

Recluses

Lu Yü, courtesy name Hongjian. Lu was upright and resolute, innately profound. Although a solitary man, there was never a day when he neglected to be trustworthy and dutiful. Indeed, his Autobiography reveals this was so. Yü described himself as intelligent and inquisitive, industrious in his focus and zeal. His resolve was absolute and endless, and he conducted himself with determination and conviction. Somber by nature, he was, however, easy-going in the company of others. He had the love of learning of Shen Zhilian, the obsession of Ruan Dongping, the tenacity and authority of Zhuang Qiyüan, and the destructive passion of Wang Changshi. Is this not worthy and virtuous? Is this not the manner of the lofty and detached? When he was raised in the Zen of Master Ji, the foremost Perfection was revealed as ending the cycle of birth and death – Nirvana. But how is this not comparable to following the footsteps of Zhi Daolin? Thus, his adherence to the Confucian canon was unwavering, and though he endured humiliation and servitude, he was unrepentant. He attended the academy on Fire Gate Mountain, built a thatched cottage on the banks of Reed Stream, and was a reclusive, independent man of ease. In the dusty world, he was once an actor and a master of entertainments, and he met celebrated high officials like Li Qiwu, Cui Guofu, and Zou Fuzi who befriended him throughout his life. Ultimately, he was summoned to court as Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent, a post that he declined. Have his works been transmitted correctly? They are most certainly preeminent and exceptional. The Book of Tang recorded that “Three days after his birth, geese came to protect him. As an adult, he cast a divination and received the character ‘gradually’ from the hexagram ‘to proceed in stages’ from which he derived his surname Lu.” In his Autobiography of the Imperial Instructor, he states, “Indeed, it is not known where he is from.” After a hundred years or more, there was then Xiyi Chen Tuan, a rare man of antiquity who received a surname. Fate is often inexplicable. A bibliography of Lu Yü’s writings are in the classics, records, and annals, and his autobiography is found in numerous compendia.

乾隆《天門縣志》

卷十七

隱逸 陸羽

陸羽字鴻漸,性介而情深,雖獨行未嘗一日忘忠孝也。觀其“自序”盡之矣。羽自言慧而通,其用功專而銳,其立志窮而不變,其為人果於自信,勇於為人而慵於周旋。有沈織廉之好學,阮東平之興致,庄漆園之解粘釋縛,王長史之終為情死。是殆庶乎?狂狷者流耶!當其養於積公之禪,名蘭勝果以証無生,何遽不若支道林之躅?乃執儒典不屈,至淪辱厮養不悔。負書火門,結廬苕溪,自位於放人佚士,同塵於伶人樂師,一時名流達官如李齊物、崔國輔、鄒夫子諸人,皆握手如平生。終以文學征於朝不赴。遺文垂后其亦矯乎?克自振拔者矣。《唐書》謂其“生三日而雁銜以來。及長,佔於‘蹇’之‘漸’而得姓名。”即“文學自傳”亦曰:“不知何許人也”。后百余年有希夷摶冒陳,得姓蓋古之異人,常有不可解於造物如斯者。所著書目在經籍志,自傳在余編。

Source

Qialong Tianmen xianzhi 乾隆天門縣志 (Tianmen County Annals of the Qianlong Reign Period, 1767; reprint Jiangsu guji chuban she江蘇古籍出版社, 1922), Zhang Biao章鑣 (js 1742, died 1768) and Zhang Xüecheng章學誠 (js 1778, 1738-1801), ch. 17.

An Anthology of Poetry and Biographical Sketches from Hubei

Chapter Twenty-eight

Tianmen

Lu Yü, courtesy name Hongjian. Yü, a man of the Kaiyüan reign period. He was awarded the offices of Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent and Great Invocator of the Court of Imperial Sacrifices, which he declined. He was upright and resolute, innately profound. Although a solitary man, there was never a day when he neglected to be trustworthy and dutiful. Indeed, his Autobiography reveals this was so. Yü described himself as intelligent and inquisitive, industrious in his focus and zeal. His resolve was absolute and endless, and he conducted himself with determination and conviction. Somber by nature, he was, however, easy-going in the company of others. He had the love of learning of Shen Zhilian, the obsession of Ruan Dongping, the tenacity and authority of Zhuang Qiyüan, and the destructive passion of Wang Changshi. Is this not worthy and virtuous? Is this not the manner of the lofty and detached? When he was raised in the Zen of Master Ji, the foremost Perfection was revealed as ending the cycle of birth and death – Nirvana. But how is this not comparable to following the footsteps of Zhi Daolin? Thus, his adherence to the Confucian canon was unwavering, and though he endured humiliation and servitude, he was unrepentant. He attended the academy on Fire Gate Mountain, built a thatched cottage on the banks of Reed Stream, and was a reclusive, independent man of ease. In the dusty world, he was once an actor and a master of entertainments, and he met celebrated high officials like Li Qiwu, Cui Guofu, and Zou Fuzi who befriended him throughout his life. Ultimately, he was summoned to court as Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent, a post that he declined. Have his works been transmitted correctly? They are most certainly preeminent and exceptional. The Book of Tang recorded that “Three days after his birth, geese came to protect him. As an adult, he cast a divination and received the character ‘gradually’ from the hexagram ‘to proceed in stages’ from which he derived his surname Lu.” In his Autobiography of the Imperial Instructor, he states, “Indeed, it is not known where he is from.” After a hundred years or more, there was then Xiyi Chen Tuan, a rare man of antiquity who received a surname. Fate is often inexplicable. A bibliography of Lu Yü’s writings are in the classics, records, and annals, and his autobiography is found in numerous compendia.

Yü wrote his Autobiography of the Imperial Instructor Lu for which the source is the New History of the Tang Dynasty by Song Zijing. According to Stories of Cause and Consequence by Zhao Lin, “Master Ji, a monk surnamed Lu from the Hidden Dragon Monastery at Jingling, found a baby boy on an embankment and raised him. Accordingly, the monk gave his last name Lu to the child.” The boy was intelligent and gifted, but at first Master Ji did not allow him to study the Confucian classics and found a hundred ways to humiliate him. But in the end, Yü was insistent and eventually went to Fire Gate Mountain to study with the academician Master Zou, and in time he became close friends with the poet monk Jiaoran. Yü’s scholarly vision was erudite and untrammeled. Witty and lighthearted, unbound by convention, he was an exemplary man of East Asia. His writings include The Bonds between Ruler and Subject, Unraveling Origins, Genealogy of Four Surnames South of the Yangzi River, A Record of Famous People from North and South, A Record of Successive Officials in Wuxing, The Interpretation of Dreams, and the Book of Tea which is his only extant work. He wrote the poem entitled Song and the verse “I have only a thousand longings, ten thousand yearnings for the western waters of the River.” In his hometown, there is Overturned Cauldron Island and the Spring of Master Lu, places for the serving and connoisseurship of tea. Yü wandered about Jianghu, the riverine south. During the An Lushan Rebellion on the Central Plains, he wrote Four Lamentations; and during the invasion of the JiangHuai region by Liu Zhan, he composed the ode, The Obscuring of Heaven.

The Imperial Instructor Lu wrote poems of linked verse with Yan Zhenqing, Wu Yün, Li E, Yang Ping, Geng Wei, Huangfu Ceng, Liu Qüanbai, and the monk Jiaoran. Though the poems are not wholly complete, the collection expresses the zenith of the age. The poem Climbing Mount Yan to View Stone Vessel Rock contains the lines, “Idle steps drawn by the deep pines, the kudzu tender and fragile to the touch.” From Singing to the Wind at the Water Pavilion, “Shaking the flagstaff, the cicada stridently shrieks, parting the curtain, all worries disappear.” From Seven Character Verse, “The gentleman, masters, and recluses of the Han all followed the teachings of Confucius of Lu, a mild yearning in admiration and in vain, how regretful the mispoken words.” From the untrammeled lines of “Opening the Border Lands, “In the old forests of the border lands, strange rocks lay scattered about” and “Deep valleys possess perilous streams and tumbled cliffs.” Accounts of the Sea and Splintered Events contains the dramatically powerful couplet from Inscription on the Spring at Kangwang Valley, “Swiftly flowing from a thousand high rocks, chasing the boat from Jiujiang.” From the especially fine literary style of Seven-Character Verse written on East Mountain at Kuaiji, “Moon-colored, the cold tide enters Shan Stream, the cries of the black apes break west of the Green Woods. The ancients followed its eastward flow, the river weed floats year after year through the emptiness.” From the poem West River in Notes on Jingling Poetry, “I do not covet wine vessels of yellow gold nor covet cups of white jade. I do not long for court matins nor long for evening audiences. I have only a thousand longings, ten thousand yearnings for the western waters of the River.” And from Sipping Tea on a Moonlit Night, “Drifting blossoms invite the traveler to drink and talk, to stay a while longer.”

湖北詩征傳略

卷二十八

天門

陸羽字鴻漸

羽,開元時人。詔授太子文學,徙太常寺太祝,不就。性介而情深,雖獨行未嘗一日忘忠孝也。觀其“自序”盡之矣。羽自言慧而通,其用功專而銳,其立志窮而不變,其為人果於自信,勇於為人而慵於周旋。有沈織廉之好學,阮東平之興致,庄漆園之解粘釋縛,王長史之終為情死。是殆庶乎?狂狷者流邪耶!乃執儒典不屈,至淪辱厮養不悔。負書火門,結廬苕溪,自位於放人佚士,同塵於伶人樂師,一時名流達官如李齊物、崔國輔、鄒夫子諸人,皆握手如平生。終以文學征於朝不赴。遺文垂后其亦矯乎?克自振拔者矣。《唐書》謂其“生三日而雁銜以來。及長,佔於‘蹇’之‘漸’而得姓名。”即《文學自傳》亦雲“不知何許人也”。后百余年有希夷摶冒陳為姓,蓋古之異人常有不可解,於造物若斯者。

羽嘗自撰《陸文學傳》,宋子京《唐書》本之。趙隣《因話錄》:“竟陵龍蓋寺僧積公陸某,於堤上得一初生兒,育之。遂從其姓”。穎悟多能,積公初不令習儒,百方挫辱而終不懈。遂至火門山從鄒夫子學。旋與皎然為莫逆交。學瞻詞逸,詼諧縱橫,東方曼倩之籌也。其遺文如《君臣契》、《源解》、《江西四姓譜》、《南北人物志》、《吳興歷官記》、《佔夢書》,《茶經》,唯《茶經》行世。嘗作《歌》雲:‘千羨萬羨西江水,獨向竟陵城下來。’”“故有覆釜洲陸子泉,皆烹茶品茶處。羽放跡江湖,當安祿山亂中原,為《四悲詩》﹔劉展窺江淮,作《天之未明賦》。

陸文學嘗與顏真卿、吳筠、李萼、楊憑、耿湋、皇甫曾、劉全白、釋皎然諸公,為聯句詩不盡可傳,然亦可匯紀以志一時之盛。《登峴山觀石尊》雲:“鬆深引閑步,葛弱供險捫。”《水亭詠風》雲:“動枓蟬爭噪, 開簾客罷愁。”《七言》雲:“漢朝舊學君公隱,魯國今從弟子科。隻自傾心慚濡煦,何曾將口恨蹉跎。”《辟疆園》逸句雲:“辟疆舊林間,怪石紛相向。”又雲:“絕壑方險尋,亂崖亦危造。”出《海錄碎事》,其《題康王谷》有“瀉從千仞石,寄逐九江船”一聯,殊有筆力。又有七絕雲:“月色寒潮入剡溪, 青猿叫斷綠林西。昔人已逐東流去,空見年年江草齊。”則在會稽東小山作也。神韻尤佳。《竟陵詩話》《西江》雲:“不羨黃金罍,不羨白玉杯,不羨朝入朝,不羨暮登台,千羨萬羨西江水,獨向竟陵城下來。”《月夜啜茗》雲:“泛花邀過客,代飲引清言。”

Source

Hubei shi zheng zhuanlüe 湖北詩征傳略 (An Anthology of Poetry and Biographical Sketches from Hubei, 1881), Ding Suzhang 丁宿章 (active 1875-1908), comp. (Xiaogan: Dingshi Jingbei caotang chuban丁氏涇北草堂出版, 1881), ch. 28.