Immortal’s Palm Tea: Preface and Poem

Immortal’s Palm Tea: Preface and Poem*

Li Bo (701-762 A.D.) of the Tang dynasty

I have heard of Jade Spring Temple near the clear streams and serried hills of Jingzhou, where all the mountain grottos possess stalactite caves, where the many tributaries of Jade Stream mingle, where the white bats are as big as crows. According to the Book of Immortals, bats were known as celestial mice. After a thousand years, their bodies turned white as snow. When perched, they hung upside down. Drinking the stalactite waters, they were long-lived. Everywhere along the stream, there is tea with stems and leaves like blue-green jade. Only Master Zhen of the Jade Spring Temple used to pick the tea to drink. He was over eighty with a complexion like peaches and plums. This tea is pure in fragrance and mellow in taste, different from other teas. Thus, it restores youth and reverses decay, enhancing longevity. While in Jinling, I saw my nephew Zhongfu who showed me several tens of tea leaves, all curled and layered, shaped like hands, and bearing the name Immortal’s Palm Tea. It is newly produced from the hills of Jade Spring Temple: nothing like it has ever been seen before. Since Zhongfu presented me with this tea and a poem, he wishes me to respond. Therefore, I have written this introduction. Hereafter, the eminent monks and great recluses will all know that Immortal’s Palm Tea began with the Zen master Zhongfu and the Buddhist layman Green Lotus, Li Bo.

Ever have I heard of Mount Jade Spring,

Of its mountain grottos filled with stalactite caves

And immortal bats as big as white crows,

All hanging down above the clear, moonlit stream.

Tea grows among the rocks

And along Jade Spring’s ceaseless flow.

Root and stem exude a rich fragrance;

One whiff nurtures flesh and bone.

Lush and voluminous, the green leaves;

Branch upon branch, row upon row.

The sun dries Immortal’s Palm,

Coddling it like Hong Ya’s shoulder.

The world has never seen the like,

But who will spread its name?

Nephew Ying, the Zen master

Presents this tea and a beautiful poem;

Both are bright mirrors embellishing ugly Wuyan,

But I am shamed by the beauty Xizi.

Even so, this morning I joyfully

Sing this song to the Heavens.

Portrait of Li Bo

唐李白

答族侄僧中孚贈玉泉仙人掌茶並序

余聞荊州玉泉寺近清溪諸山,山洞往往有乳窟,窟中多玉泉交流,其中有白蝙蝠,大如鴉。按《仙經》,蝙蝠一名仙鼠,千歲之后,體白如雪,棲則倒懸,蓋飲乳水而長生也。其水邊處處有茗草羅生,枝葉如碧玉。惟玉泉真公常採而飲之,年八十余歲,顏色如桃李。而此茗清香滑熟,異於他者,所以能還童振枯,扶人壽也。余游金陵,見宗僧中孚,示余茶數十片,拳然重疊,其狀如手,號為“仙人掌茶”。蓋新出乎玉泉之山,曠古未覿。因持之見遺,兼贈詩,要余答之,遂有此作。后之高僧大隱,知仙人掌茶發乎中孚禪子及青蓮居士李白也。

常聞玉泉山

山洞多乳窟

仙鼠如白鴉

倒懸清溪月

茗生此中石

玉泉流不歇

根柯灑芳津

採服潤肌骨

叢老卷綠葉

枝枝相接連

曝成仙人掌

似拍洪崖肩

舉世未見之

其名定誰傳

宗英乃禪伯

投贈有佳篇

清鏡燭無鹽

顧慚西子妍

朝坐有餘興

長吟播諸天 Continue Reading →

The Sultaness Head

Thomas Garway and the Marketing of Tea in Seventeenth Century London

Introduction

In the history of English tea, the name Thomas Garway was intimately linked with two London coffee houses. The first was the Sultaness Head in Sweetings Rents, and the second, Garraway’s Coffee House in Exchange Alley. The historical treatment of Thomas Garway and his relationship to the Sultaness Head was uneven, and some early writings did not even associate the man with the place. More recent scholarship, principally that of Markman Ellis of the University of London, shows that the proprietor of the Sultaness head was indeed Thomas Garway, the first to offer tea to the English public. The account of Garway is an intriguing tale of tea, one immensely rich in detail and replete with unexpected twists and turns.

Contrary to modern notions, Garway was no aproned shopkeeper but in fact the scion of a great mercantile house, a guildsman, and above all an entrepreneur. Similarly, the Sultaness Head was not merely a coffee house but instead a satellite of commerce and finance in close orbit to the Royal Exchange and the goldsmith banks. Straddling the turbulent periods of the Interregnum and the Restoration, Thomas Garway and the Sultaness Head appeared and prospered in a time of astonishing fortune and extraordinary calamity. Continue Reading →

No Harm in Tea

Tea received mixed reviews in seventeenth century Europe. Touted by herbalists and healers as a miraculous cure for nearly every ailment, tea contended with the strong and formidable opposition of medical conservatives throughout the Continent. According to the German doctor Simon Pauli and the French physician Guy Patin, its fiercest critics, tea was the bane of medicines, hastening death to all who partook. But tea had vocal advocates, staunch allies who rallied in print and practice, putting up a stiff defense of the brew to the benefit of general health, commerce, and sometimes personal gain.

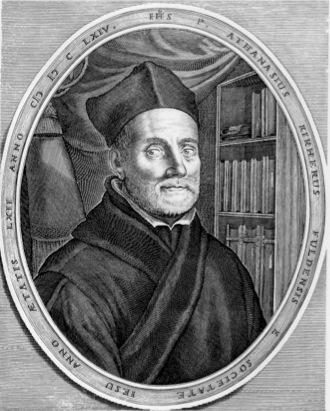

In Rome, the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher had heard of tea but did not at first believe in its medicinal efficacy. On drinking tea, Kircher was astonished and amended his opinion to become a champion of the leaf:

“It is a plant of great virtue, the likes of which, if I had not experienced it myself upon the invitation of some Fathers of our order, I would never have been led to credit, for joined to its diuretic faculty, it wonderfully relaxes every blockage of the kidneys and dissipates the heaviness of the head, so that literary men, or others who are compelled by the magnitude of their labors to stay up late at night, find no more noble or fitting remedy in all of nature, and although at first its taste is watery and somewhat bitter, in time it not only loses its unpleasantness, but soothes so well the itchings of the throat, that those who have taken up this drink find it hard to do without.”

Kircher went on to compose one of the most influential books on China. Published in 1667, China Illustrata was an encyclopedic work that included natural history and the mention of the tea plant:

“There is the plant called Cha, which not being able to contain itself within the bounds of China, hath insinuated itself into Europe: it aboundeth in divers regions of China, and there is great difference, but the best and most choice is in the Province Kingnan [sic], in the territory of the city Hocicheu [sic]. The leaf being boiled and infused in water, they drink it hot as often as they please: it is of a diuretic faculty, much fortifies the stomach, exhilarates the spirits, and wonderfully openeth all the nephritick passages or reins; it freeth the head by suppressing of fuliginous vapours, so that it is a most excellent drink for studious and sedentary persons, to quicken them in their operations; and though, at the first, it seemeth insipid and bitter, yet custom maketh it pleasant; and though the Turkish coffee administer the like cordiality, and the Mexican chocolate be another excellent drink, yet tea, if the best, very much excelleth them both, because, that chocolate in hot seasons inflameth more than ordinary, and coffee agitateth choler; but tea in all seasons hath one and the same effect.”[1] Continue Reading →

Happy for the Arrival of Lu Yü

Li Ye (713-784 A.D.) of the Tang dynasty

Lying Ill above the Lake, Happy for the Arrival of Lu Yü

Parting many wintry moons ago,

You now come in bitter spring mists,

Happening upon me still sick abed:

I yearn to speak, but first my tears fall.

Compelled by Tao Qian’s wine,

I hastily chant a poem by Xie Lingyün.

All of a sudden, I’m perfectly intoxicated…

More than this, is there anything else? Continue Reading →

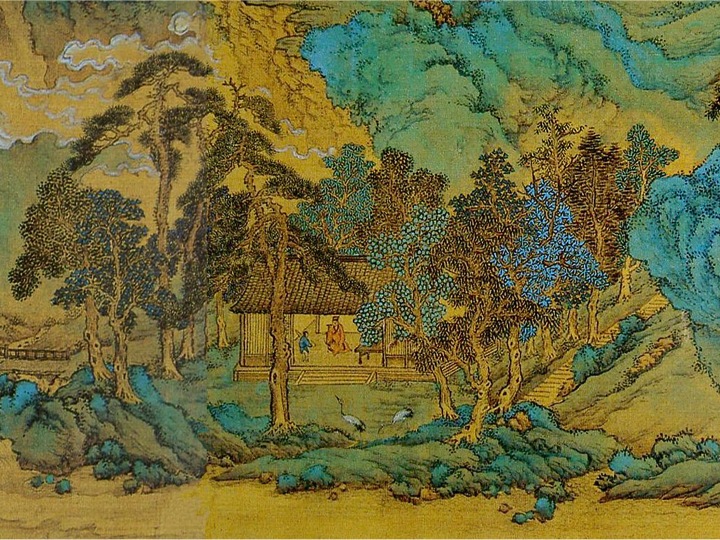

Deer Hermitage

Wang Wei (701-761 A.D.) of the Tang dynasty

Wheel River Collection

Deer Hermitage

Empty mountains – seeing no one

Yet hearing echoes – someone’s voice

Late light penetrates deep woods

Reflecting upon dark green moss

王維

輞川集

鹿柴

空山不見人

但聞人語響

返景入深林

復照青苔上

Tea and the Italian Renaissance

The earliest European accounts of tea were written in Italy during the late Renaissance when the spirited rebirth of art and culture in the sixteenth century was most evident in Rome, Venice, and Naples, all cities of great wealth, power, and refinement. Knowledge of Asia amassed on the Italian Peninsula through its influential political, religious, and economic institutions – the Vatican, trade, and banking. Church reports and correspondence from Asia were compiled and published in Rome – their descriptions of tea found vivid complements in Neapolitan histories of the East and colorful Oriental travelogues from Venice.

Tea and Jesuits III

The earliest Western account of chanoyu 茶の湯 was written by the Jesuit João Rodrigues, a serious practitioner of tea in the late sixteenth century. Born in Portugal, Rodrigues landed in Japan in 1577 at age fifteen and spent over thirty years in the islands as a missionary, scholar, and diplomat. Trained by the Jesuits in Japan and fluent in Japanese, his function as translator facilitated his entry into the rarified levels of Japanese society where he met many of the most influential political figures of the day. His personal practice of tea served to advance him within Japanese circles at a time when aesthetic interests and intellectual sophistication were de rigueur. Well versed in both Western and Eastern cultures, he was a sympathetic and knowledgeable bridge between the two.

Rodrigues wrote extensively about chanoyu in his treatise on Japanese tea, Arte del Cha.[1] He identified tea with extremely high production standards, quality, and great cost, describing in detail the annual harvest from Uji, which produced the finest tea for the exclusive use of the shogun, and further observing, “the best type of tea, used in gatherings of nobles and rich men, is very expensive…”[2]

His writing showed the depth of his understanding of tea, including the philosophical and social bases for chanoyu. He explained not only the methods and procedures of the art, but also the deeply Zen search for the “contemplation of things and nature” through tea and its “emphasis on frugality and moderation, without any slackness, indolence, or effeminacy.”[3] He dwelt on the purpose of tea as “courtesy, breeding, moderation, peace of body and soul, humility, without pomp or splendor” but stressed again “the people who practice cha are nobles or lords because the expense incurred therein is indeed great.”[4] Continue Reading →

Tea and Jesuits II

In 1561, Juan Fernández, a lay member of the Society of Jesus, recorded the adoption of tea at the Jesuit residence where Damien, a young Japanese convert, “has the task of always having a kettle of hot water ready, which he gives to all the visitors and to those in the residence who want it. This the custom of the country.”[1] Although not entirely clear, the Fernández commentary may be the first suggestion of Europeans regularly taking tea. More certain were the accounts of the Jesuit Luis d’Almeida who noted that “the Japanese are very fond of an herb agreeable to the taste, which they call chia”[2] and described tea as a “delicious drink once one becomes used to it”[3] as if making an enthusiastic recommendation of the herb.

Luis d’Almeida was a Portuguese physician who arrived in Japan in 1556 aboard a merchantman.

Tea and Jesuits I

The birth of the Jesuit mission in Asia was intimately linked to the Lisbon royal court and Portuguese ambitions for empire. In the first voyage to the East Indies, Portugal sent a small fleet under the command of Vasco da Gama.

His forces landed in India at Calicut, “the City of Spices” in 1498, marking a harsh and persistent Portuguese presence along the west coast of the subcontinent that lasted for centuries. Defeating the Bijapur sultanate and capturing Goa in 1510, conquistadors established the port city as the administrative seat of Portuguese India; explorers then ventured to Malacca, the Spice Islands, and China, where the Portuguese acquired the island port of Macao. Continue Reading →

Looking for Lu Hongjian

Jiaoran (730-799 A.D.) of the Tang dynasty

Looking for Lu Hongjian but Not Finding Him

You moved beyond the city wall,

Where the rural path crosses mulberry and hemp,

Near a planted hedge of chrysanthemum,

Not blooming, though autumn has come.

Knocking on your door, no answer, not even the bark of a dog.

Wishing to leave, I asked your neighbor to the west.

He said you go off into the mountains,

Returning with each setting sun.

Picking Lotus

Xiao Gang (a.k.a. Emperor Jianwen di, reign 549-551) of the Liang dynasty

Picking Lotus

Late sun warms the deserted jetty,

Picking lotuses by evening’s glow.

Wind rising; the lake crossing, hard.

So many lotuses, undiminished by the harvest.

The oar moves, the petals fall.

The boat sways, the white egret takes flight.

Lotus silk entwines about our wrists,

Water caltrop pulls at our sleeves.

Cha and Te

The character 茶 for tea was pronounced differently in different Chinese dialects. Seafaring merchants sailing from their native ports in southern China spoke a number of local and regional languages, including the widely disparate Cantonese of Guangdong province and the Amoy of Fujian. While trading in Southeast Asian waters, along the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian island of Java, the Chinese encountered early European traders at the port cities of Malacca, Bantam, and Jayakarta and introduced the Westerners to tea. When speaking of the plant and leaf, the Chinese used the distinct languages of their different provinces.

The Cantonese pronounced the word tea as cha.[1] Cha also happened to be the spoken word for tea in the widespread Mandarin dialect. Linguistically, Cantonese and Mandarin together covered nearly three quarters of the country, that is to say, cha was the dominant pronunciation for tea throughout China. Tea as 茶 and cha extended beyond the continent to Korea and Japan, where the plant and herb were introduced from China as an important commodity and a feature of high culture and foreign diplomacy. Continue Reading →