Tea and the Italian Renaissance

The earliest European accounts of tea were written in Italy during the late Renaissance when the spirited rebirth of art and culture in the sixteenth century was most evident in Rome, Venice, and Naples, all cities of great wealth, power, and refinement. Knowledge of Asia amassed on the Italian Peninsula through its influential political, religious, and economic institutions – the Vatican, trade, and banking. Church reports and correspondence from Asia were compiled and published in Rome – their descriptions of tea found vivid complements in Neapolitan histories of the East and colorful Oriental travelogues from Venice.

Vatican Rome exerted considerable influence throughout the Continent and discrete parts of Asia. In the East Indies, the militant evangelism of the Society of Jesus joined forces with conquistadores and merchant adventurers. In Europe as in Asia, the mutual interests of the Vatican and the royal courts at Lisbon and Madrid coincided when much of Italy came under the rule of Habsburg Spain. As the capital of the Roman Catholic faith, the Vatican commanded a degree of obedience from nearly all Western kings and queens. Furthermore, the language of the Holy See was an important source of Rome’s power to communicate and control. Latin remained as it had for centuries the lingua franca of educated Europe, and Italian was the most widely understood language. Trafficking in diplomacy and intrigue, the city of Rome was the focal point for the collection of foreign intelligence and the dissemination of knowledge. The Apostolic Nuncio to Goa, the Vatican’s ambassador in the Indies, wrote official letters to Italy, sending reports via the annual East Indies ship returning to Lisbon. Transmitted across the Mediterranean to Ostia and up the Tiber River to Rome, diplomatic and mission letters circulated and were subsequently published in Italian and Latin by the Vatican to announce the success of the Church in Asia and spread information on the extraordinary finds of the East.

In 1545, Naples was the most populous city in Europe and a major port on the Mediterranean Sea. Possessed of a vibrant maritime history dating back to Greco-Roman times, Naples was a trade and cultural center of the ancient and medieval worlds, and nearby Salerno was equally renowned for its school of medicine. In 1224, King Frederick II, the Holy Roman Emperor, founded the University of Naples, one of the oldest academic institutions in Europe. Two hundred years later, as Asian goods flowed westward along the Silk Road secured by the peace of the Mongols, King Robert the Wise sated his curiosity for the East by acquiring for his great library a new work, About the Extraordinary Things in the Country of the Great Khan, concerning the travels of the Venetian Marco Polo to China. As the capital of the Kingdom of Naples, the city was the destination of European and Asian emissaries, travelers, and correspondence sailing to Italy. During the sixteenth century, extensive construction and renovation of buildings, shipyards, and fortifications were undertaken by the viceroys appointed by Hapsburg Spain. The wealthy patrons of the city created art collections, museums, libraries, and botanical gardens, making Naples one of the great artistic and cultural capitals of Europe.

Strategically situated on the Adriatic, Venice was once the most powerful city in Europe, dominating commerce by land and sea between the West and the Eastern empires of Byzantium and the Islamic world. With the loss of Constantinople to the Turks and three decades of war with the Ottoman Empire in the fifteenth century, the power of Venice declined, eclipsed by the Iberian ascent in Asia and the New World. Yet, even after the opening of the Portuguese sea routes to the East Indies ended the Venetian monopoly on Asian trade, Venice remained a great center of international exchange. As the traditional portal to the Orient, Venetian influence gained ground and prospered. The Venetian naval complex, the Arsenal, remained the greatest shipyard in the Mediterranean and Europe, producing the latest ship designs, armaments, and equipment. Throughout northern Italy, Venice, Florence, and Genoa were home to powerful banking families financing European trade: del Banco, Medici, and Bardo. Foreign envoys and merchants traveling westward overland from the Orient to the capitals and courts of Europe began their Continental tours in Venice which became privy to international affairs of state and commercial interests. Indeed, Venice competed with Rome and other European cities in nearly every way. Knowledge spiraled into Venice, concentrated, and then swirled out in the form of books to all parts of the Continent. Venetian merchants, scholars, and printers excelled in the translation, collation, and publication of information. Its publishing houses were well established in the propagation of data and opinion: “before 1501, Venice printed more books than any other European city, and was rivaled in Italy only by Rome.”[1]

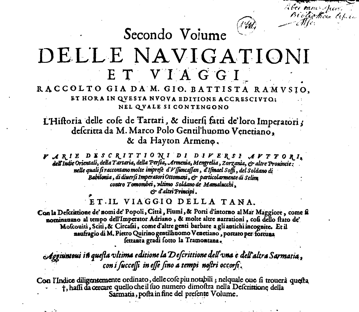

It was in Venice that the first Western record of tea occurred. The Venetian magistrate Giovanni Battista Ramusio exemplified the intense curiosity with which learned Italians viewed the East. A statesman, historian, and linguist, Ramusio translated various European travel accounts of Asia into Italian. His monumental work of three volumes, Delle Navigationi e Viaggi (Voyages and Travels, 1550-1559), spread revelations of the Orient throughout the Continent. A great raconteur, he entertained readers with tales of personal encounters with foreigners from the East.

While attending a party on the island of Murano in the Venetian Lagoon, Ramusio chatted with one “Chaggi Memet,”[2] a Persian merchant from Yazd[3] traveling in Italy having just returned from China with rhubarb. Since ancient times, the West considered the root of Chinese Rheum palmatum as a purgative and medicine against numerous ailments: as no other form of the plant would do, the European trade in Chinese rhubarb was extremely lucrative. But instead of praising rhubarb, Chaggi Memet surprised Ramusio by relating that the Chinese thought little of the herb and used it as incense, fuel, and horse fodder. As the Persian recounted the curative powers of tea, the Venetian listened:

“Then seeing the great pleasure that I beyond the rest of the company took in his stories, he told me that over all the country of Cathay they made use of another plant, or rather of its leaves. This is called by those people Chiai Catai [China tea], and grows in the district of Cathay, which is called Cacianfu [Sichuan]. This is commonly used and much esteemed over all those countries. They take of that herb whether dry or fresh, and boil it well in water. One or two cups of this decoction taken on an empty stomach removes fever, head-ache, stomach-ache, pain in the side or in the joints, and it should be taken as hot as you can bear it. He said besides that it was good for no end of other ailments which he could not then remember, but gout was one of them. And if it happens that one feels incommoded in the stomach from having eaten too much, one has but to take a little of this decoction and in a short time all will be digested. And it is so highly valued and esteemed that every one going on a journey takes it with him, and those people would gladly give (as he expressed it) a sack of rhubarb for an ounce of Chiai Catai.”[4]

In Rome, the Vatican sanctioned publication of the Jesuit reports from Japan for the promotion of Catholic interests in Europe, especially in the north where the books demonstrated to Catholics and Protestants alike the activities of a vigorous and prosperous Church. When published in 1552, the letters of Francis Xavier and Alessandro Valignano met with requests for further information. The Superior General of the Society, Ignatius Loyola himself, expressed the desire of Roman readers for the inclusion of “the cosmography of these regions” and as for “other things that may seem extraordinary, let them be noted, for instance, details about animals and plants that either are not known at all, or not of such size, etc…”[5] The Jesuit accounts of tea fulfilled in great measure the curiosity of European readers about the exotic plants, medicines, and customs. Chanoyu, the Japanese ceremonial service of tea, was particularly noteworthy. In 1591, the Jesuit Alessandro Valignano, the powerful Visitor of Missions in Asia, visited the Christian lord and tea adept Gamō Ujisato in the company of João Rodrigues, the accomplished Jesuit practitioner of chanoyu.[6] Just ten years before, Valignano had encouraged the use of tea to further the religious and commercial concerns of the Society, instructing the Jesuits in Japan to observe chanoyu, in welcoming visiting Japanese lords and officials.

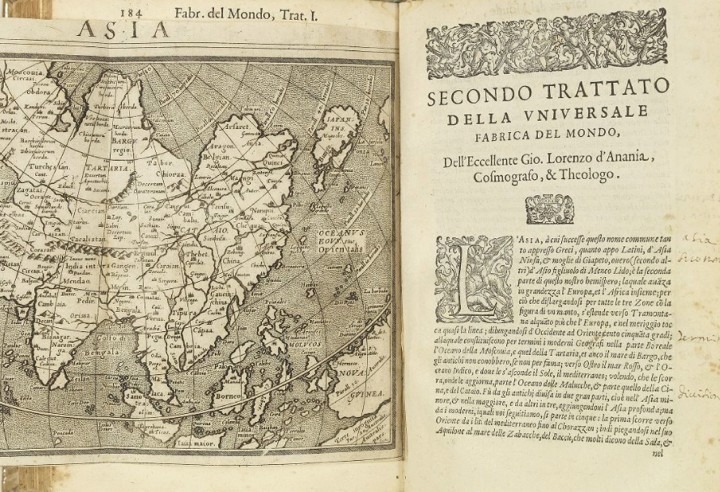

In time, the Vatican letters and Ramusio’s collection of travelogues were superseded by histories, including the comprehensive, four-volume work L’ Universale fabrica del Mondo published in 1576 by the Neapolitan academic Giovanni Lorenzo d’Anania. His second treatise of world history dealt with the contemporary knowledge of Asia, recording even the surprising arrival of three Chinese merchants in Naples during their journey to Spain and other European states. He wrote in fascination about the natural wonders of the Far East, both flora and fauna, and marked tea as a Japanese substitute for alcohol: “… all those who do not take wine, but instead, drink water with a very soft powder, they call Chiam…”[7]

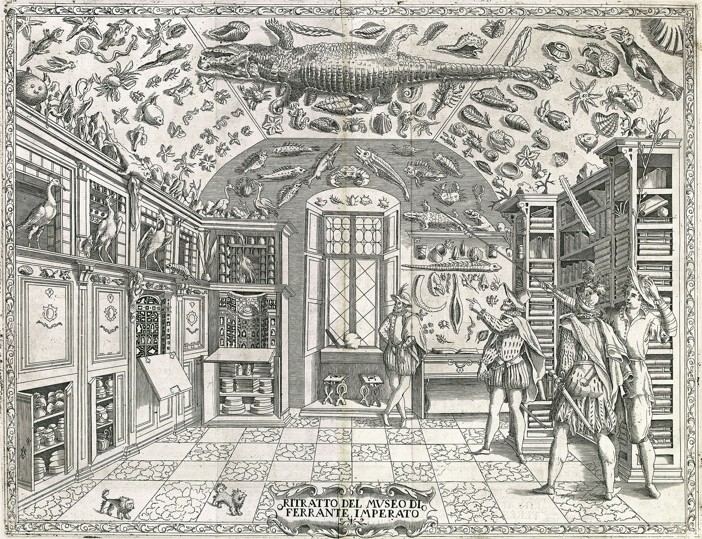

Perhaps he described the texture of tea as “dolce” or “soft” after having seen and taken the herb’s finely ground, powdery form at the literary salon of Ferrante Imperato, the Neapolitan apothecary and naturalist.[8] Imperato was famous for his cabinet of curiosities, a specimen collection of natural history housed in his home in the Palazzo Gravina and illustrated in his Dell’Historia Naturale of 1599.[9] As a noted pharmacist, Imperato imported drugs from the Indies, including rhubarb from China as well as Chinese and Japanese teas.

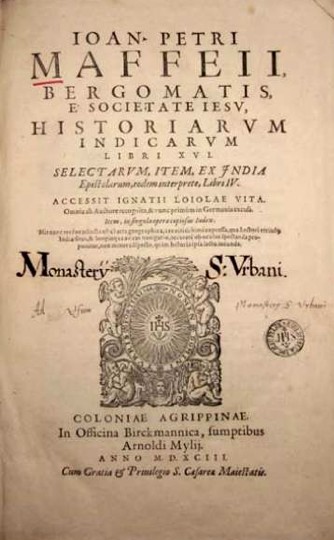

In 1588, Historiarum Indicarum Libri XVI, a Latin synthesis of the Jesuit mission in Asia, was written by the Jesuit author Giovanni Pietro Maffei in which he described the Chinese use of tea: “Although they do not extract wine from the vines as we do, but have a custom of preserving the grapes as a kind of condiment for the winter, they yet press out of a certain herb, a liquor which is very healthy which is called Chia, and they drink it hot, as do the Japanese. And the use of this causes them not to know the meaning of phlegm, heaviness of the head, or running of the eyes, but they live a long and happy life, without pain, or infirmity of any sort.”[10] Printed in Florence, the Historiarum was quickly reissued and subsequently translated into Italian and French for wide distribution throughout Europe.[11] By 1589, the Catholic philosopher Giovanni Botero confidently described tea in his history of the world. Writing of the Chinese and sobriety, “They have also an herbe, out of which they presse a delicate iucye, which serves them for drincke instead of wyne. It also preserves their health, and frees them from all those evils, that the immoderate use of wyne doth breed unto us.”[12] For Japan, Botero dwelt on the art of tea which he described as dear and delicate: “Water mixt with a certaine precious powder which they use, they account a daintie beverage: they call it Chia.”[13]

Figures

1.

Gaspar van Wittel (Dutch, 1653-1736 A.D.)

Tiber at Castel Sant’Angelo

Oil on canvas

Galleria Nazionale d’Arte

Antica, Italy

2.

Gaspar van Wittel (Dutch, 1653-1736 A.D.)

Coast of Naples Viewed from the Sea, 1719

Oil on canvas

Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti

Florence, Italy

3.

Gaspar van Wittel (Dutch, 1653-1736 A.D.)

Saint Mark’s Basin with the Molo, Piazzetta and Palazzo ducale

Oil on canvas

Museo del Prado

Madrid, Spain

4.

Title page, detail

Giovanni Battista Ramusio (Italian, 1485-1557 A.D.)

Delle Navigationi e Viaggi (Voyages and Travels, 1550-1559)

Venice: Tomasso Giunti, 1583

5.

Rhubarb

Giovanni Battista Ramusio (Italian, 1485-1557 A.D.)

Delle Navigationi e Viaggi (Voyages and Travels, 1550-1559)

Venice: Tomasso Giunti, 1583

6.

Gaspar van Wittel (Dutch, 1653-1736 A.D.)

Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, 1700-1710

Oil on canvas

Kunsthistorisches Museum

Vienna, Austria

7.

Second Treatise, detail

Giovanni Lorenzo d’ Anania (Italian, 1545-1609 A.D.)

L’ Universale fabrica del Mondo

Venice: I Vidali, 1576

8.

Museum of Ferrante Imperato

Ferrante Imperato (Italian, 1550-1631 A.D.)

Dell’Historia Naturale libre XXVIII

Naples, 1599

9.

Title page

Giovanni Pietro Maffei (Italian, 1533–1603 A.D.)

Historiarum Indicarum libri XVI.

Cologne: Arnold Mylius, 1593.

formerly St. Urban Monastery library

Notes

[1] Donald F. Lach, “The Printed Word,” Asia in the Making of Europe (Chicago: The University of Chicago, 1965), vol. I, ch. IV, p. 149.

[2] Also known as Hajji Mahommed (Persian, 16th century).

[3] Yazd, the capital of Yazd province, Iran. Samuel Adrian Miles Adshead, China in World History (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), p. 223.

[4] Henry Yule (English, 1820-1889) et al., “Hajji Mahomed’s Account of Cathay as Delivered

to Messer. Giov. Battista Ramusio,” Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China (London: Hakluyt society, 1866), XVIII, pp. cxiv-cxvi; cf. Giovanni Battista Ramusio (Italian, 1485-1557), “Dichiarazione D’alcuni Luoghi Ne’ Libri Di Messer Marco Polo, Con L’istoria Del Reubarbaro (Declaration of certain places from the book of Master Marco Polo, with the history of rhubarb) and “Index to the Second Volume,” Delle Navigationi e Viaggi (Voyages and Travels, 1550-1559) (Venice: Tomasso Giunti, 1583) vol. II, fo. 15, p. 16.

[5] Donald Lach, “The Christian Mission,” Asia in the Making of Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965), vol. 1, bk. 1, ch. 5, p. 318.

[6] Michael Cooper, “The Early Europeans and Tea,” Tea in Japan: Essays on the History of Chanoyu, Paul Varley and Kumakura Isao, eds. (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1989), p. 119.

[7] Giovanni Lorenzo d’ Anania (Italian, 1545-1609 A.D.), L’ Universale fabrica del Mondo (Venice: I Vidali, 1576 A.D.), p. 236.

[8] Donald Lach, “Italian Literature,” Asia in the Making of Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977), vol. 2, bk. 2, ch. 6, p. 231.

[9] See Ferrante Imperato (1550-1631 A.D.) Dell’Historia Naturale libre XXVIII (Naples, 1599).

[10] Giovanni Pietro Maffei, S.J. (Italian, 1533–1603), Le istorie dell’ Indie Orientali (Historiarum Indicarum libri XVI, Paris, 1572, Florence, 1588, and Cologn, 1589), Francesco Serdonati, trans. (Bergamo, 1749), bk. VI, p. 171.

[11] Donald F. Lach, “Jesuit Letterbooks and Histories,” Asia in the Eyes of Europe: Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries (Chicago: The University of Chicago Library, 1991), pp. 15-16. For the Society’s publications printed in Macao and Nagasaki, see Luís Filipe Barreto, “Macao: An Intercultural Frontier in the Ming Period,” History of mathematical sciences: Portugal and East Asia II, Luís Saraiva, ed. (Singapore: World Scientific, 2004), pp. 1-22.

[12] Giovanni Botero (Italian, 1544-1617), A Treatise Concerning The Causes Of The Magnificencie And Greatness Of Cities (1589), Robert Peterson (fl. 1576-1606), trans. (London: R. Ockould ; H. Tomes, 1606), book 2, ch. 11, p. 75.

[13] Giovanni Botero (Italian, 1540-1617), The Worlde, or an Historicall Description of the Most Famous Kingdoms and Commonweales therein, Robert Johnson (fl. 1586-1626)], trans. (London, 1601), p. 216.