Biographies of Lu Yü: Translations and Texts

Transmitted Records of the Great Tang Dynasty

Author unknown, 9th century C.E.

Number twenty-four

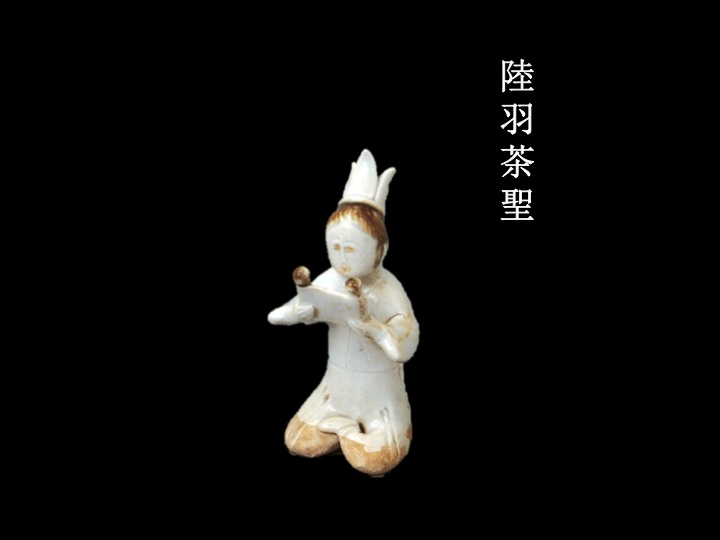

Lu Hongjian was fond of tea. He wrote the Book of Tea in three volumes; the book was popular in its time. It was common for the tea guilds to commission pottery kilns to make porcelain figures of him to set upon the brazier and cauldron to exert his influence as the God of Tea. During business, either leaf tea was offered to the figure or brewed tea was used to pour over it.

大唐傳載

不著撰人名氏, 第九世纪公元

第二十四

陸鴻漸嗜茶,撰《茶經》三卷,行於代。常見鬻茶邸燒瓦瓷為其形貌,置於竈釜上,左右為茶神。有交易則茶祭之,無則以釜湯沃之。

Li Zhao (flourished circa 818-821 C.E.)

Supplement to the Dynastic History of the Tang

Chapter two

“Lu Yü takes a surname and a given name”

A Buddhist monk from Jingling discovered a foundling boy on a riverbank and raised him as his disciple. When he was a little older, the boy divined the Book of Changes and received the hexagram jian 漸 from the hexagram jian 蹇 and the oracular words: “Hong jianyü lu, qi yü keyong wei yi, The wild goose gradually draws near land, its feathers can be used for rites.” Thus, he took the surname Lu, the given name Yü, and the sobriquet Hongjian.

Yü possessed erudition and many ideas, and so it was a shame that only one thing completely engaged his genius – namely, spreading the art of tea. The potters of Gong county made many porcelain figures of him, calling them each Lu Hongjian. When someone bought many tens of tea implements from a shop, he got a Hongjian figure. When city tea traders did not make a profit, they then poured tea over it. In the Jianghu region, Yü was called Master Jingling. In the Nanyüe region, he was called Old Man Mulberry. Yü had a close friendship with Yan Lugong and was a friend of Master Xüanzhen, Zhang Zhihe. When he was young, he worked for the Zen master Zhiji. One day, Yü heard that the Zen master had passed away. He wept in deep lament and composed a poem to express his feelings:

“I do not desire cups of white jade

Nor covet wine vessels of yellow gold.

I do not yearn for court matins

Nor long for evening audiences.

I do have a thousand yearnings, ten thousand longings

For the western waters of the River

Flowing just beyond the walls of Jingling.”

Lu Yü died at the end of the Zhenyüan reign period.

李肇撰

唐國史補

卷中

陸羽得姓名(氏)

竟陵僧有於水濱得嬰兒者,育為弟子,稍長,自筮得《蹇》之《漸》繇曰:「鴻漸於陸,其羽可用為儀。」乃令姓陸名羽,字鴻漸。羽有文學,多意思,恥一物不盡 其妙,茶術尤著。鞏縣陶者多為甆偶人,號陸鴻漸,買數十茶器得一鴻漸,市人沽茗不利,輒灌注之。羽於江湖稱「竟陵子」,於南越稱「桑薴翁」。與顏魯公厚 善,及玄真子張志和為友。羽少事竟陵禪師智積,異日在他處聞禪師去世,哭之甚哀,乃作詩寄情,其略云:「不羨白玉盞,不羨黃金罍。亦不羨朝入省,亦不羨暮 入臺。千羨萬羨西江水,曾向竟陵城下來。」貞元末卒。

Zhao Lin (jinshi degree, 834 C.E.)

Stories of Cause and Consequence

Chapter three

Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent Lu Hongjian was named Yü. His ancestry is unknown. A monk from the Longxing Monastery at Jingling, who was surnamed Lu, found a baby boy on an embankment and raised him. Accordingly, he gave his last name Lu to the child. When the boy was grown, he was intelligent, gifted, and accomplished. His erudition was imaginative and his words forceful. In debate, he was witty and articulate. In the evening, he was an expansive and fine companion.

Other narratives of his life include those of Master Cao on the maternal grandfather’s side of the Yü family; the Yang family in-laws; Cao Huitan, whose sobriquet is Zhongyong, on the maternal grandfather’s side of the Hong family. Those friendships were sincere and profound. Maternal grandfather kept a letter composed by Master Lu.

By nature, Lu Yü was fond of tea and introduced the art of tea. To this day, families of the tea guilds commission pottery figures of his likeness and set them among the braziers, saying “That which is felicitous to tea, attains prosperity.”

I still remember knowing, when I was young, an old monk from Fuzhou who was a disciple of Brother Lu. He always chanted

“I do not desire wine vessels of yellow gold

Nor covet cups of white jade.

I do not yearn for court matins

Nor long for evening audiences.

I do have a thousand yearnings, ten thousand longings

For the western waters of the River

Flowing just beyond the walls of Jingling.”

and captured all of the emotion of Brother Lu’s poem.

趙璘撰

因話錄

卷三

太子陸文學鴻漸名羽,其先不知何許人。竟陵龍興寺僧,姓陸,於堤上得一初生兒,收育之,遂以陸為氏。及長,聰俊多能,學贍辭逸,詼諧縱辯,蓋東方曼倩之 儔。與餘外祖戶曹府君,外族柳氏,外祖洪府戶曹諱澹,字中庸,別有傳。交契深至。外祖有牋事狀,陸君所撰。性嗜茶,始創煎茶法,至今鬻茶之家,陶為其像, 置於煬器之間,雲宜茶足利。余幼年尚記識一復州老僧,是陸僧弟子。常諷其歌云:「不羨黃金罍,不羨白玉杯,不羨朝入省,不羨暮入臺。千羨萬羨西江水,曾向 竟陵城下來。」又有追感陸僧詩至多。

Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072 C.E.) and Song Qi (998-1061 C.E.), compilers

New Dynastic History of the Tang, 1060 C.E.

Chapter One hundred ninety-six

Historical Biography, Chapter One hundred twenty-one

Eremites

Lu Yü, whose sobriquet was Hongjian (an alternate given name was Ji and the sobriquet was Jici), a native of Jingling, Fuzhou. His paternity was unknown, but it was said that there was a monk who discovered him on a riverbank and raised him. When he was older, he used the Book of Changes to divine the hexagram jian 漸 from the hexagram jian 蹇 which read: “Hong jianyü lu, qi yü keyong wei yi, The wild goose gradually draws near land, its feathers can be used for rites.” And so, he took Lu as his surname as well as his given name and sobriquet from it.

When he was young, his master taught him Buddhist scripture, to which he responded, “To end relations with one’s brethren and sever posterity, do these fulfill the obligations of filial piety?” His master was furious and made him handle manure to repair the plaster as punishment. He made him herd thirty head of cattle, but Yü secretly used a bamboo stick to practice writing characters on the bovines’ backs. He obtained a copy of “Ode on the Southern Capital” by Zhang Heng, but he could not read it; and so, he knelt repectfully, imitating the file of schoolboys, mumbling as if reading fervently. His master restrained him, ordering him to pull rank weed and grass. Prevented from learning characters, he became befuddled, as if at a loss, insufferably passing each day. His master whipped him, making him moan, “The months and years are passing by; how will I ever survive not knowing writing and books?” Sobbing unbearably, he ran away to hide, becoming an actor and writing several thousand jokes and japes. During the Tianbao reign period, officials of Fuzhou appointed Yü master of entertainments at a banquet. Governor Li Qiwu recognized his talent, rewarding him with books, and recommending him to boarding school at Mount Huomen.

In appearance, he was ugly. He stuttered but was persuasive. Hearing people do good, he felt good. Seeing people oblivious and foul, he admonished the most offensive. When amongst friends but happened to think of something, he withdrew aside and departed, leaving people to wonder if he was angry. When devoted to someone, rain and snow, tigers and wolves could not force him to forsake him. At the beginning of the Shangyüan reign period, he went into seclusion along the Tiaoxi Stream. He called himself Old Man Mulberry and closed his door to write books. Alone in the wilds, he chanted out loud, knocking about the trees, wandering aimlessly, wretched and weeping before returning home. So then, he was known as the modern day Jieyü. After a long time, he received an official post by imperial decree, and Yü became Imperial Instructor of the Heir Apparent and was appointed Great Supplicator at the Court of Imperial Sacrifices. He declined the offices. At the end of the Zhenyüan reign period, he died.

Lu Yü was fond of tea. He authored the Book of Tea in three chapters, explaining the origins of tea, its methods, implements and equipage, and especially its preparation so that All under Heaven knew the virtues and wisdom of drinking tea. At the time, the tea guilds commissioned a ceramic figure of Yü to set among the braizers to offer libations to it as the God of Tea. There once was a Chang Boxiung, who because of Yü’s revelations, zealously extolled the merits of tea. The Censor-in-Chief Li Jiqing made an imperial tour of inspection of Jiangnan and stopped in Linghuai. He knew that Chang Boxiung excelled at brewing tea and so summoned him. Boxiung carried his implements in front of him, and because of this, Jiqing drank two bowls of tea. Upon reaching Jiangnan, someone recommended Yü to him, and so he summoned him. Dressed in rustic clothes, Yü entered ahead of his equipage, and therefore Jiqing regarded him with contempt. Yü blamed him, and in revenge wrote The Ruination of Tea. Later, tea became the fashion, and in time, even the Uighurs entered the capital, driving their horses to market for tea.

歐陽修 宋祁撰

新唐書

卷一百九十六

列傳第一百二十一

隱逸

陸羽,字鴻漸,一名疾,字季疵,複州竟陵人。不知所生,或言有僧得諸水濱,畜之。既長,以《易》自筮,得《蹇》之《漸》,曰:「鴻漸於陸,其羽可用為儀。」乃以陸為氏,名而字之。

幼時,其師教以旁行書,答曰:「終鮮兄弟,而絕後嗣,得為孝乎?」師怒,使執糞除圬塓以苦之,又使牧牛三十,羽潛以竹畫牛背為字。得張衡《南都 賦》,不能讀,危坐效群兒囁嚅若成誦狀,師拘之,令薙草莽。當其記文字,懵懵若有遺,過日不作,主者鞭苦,因歎曰:「歲月往矣,奈何不知書!」嗚咽不自勝,因亡去,匿為優人,作詼諧數千言。

天寶中,州人酺,吏署羽伶師,太守李齊物見,異之,授以書,遂廬火門山。貌侻陋,口吃而辯。聞人善,若在己,見有過者,規切至忤人。朋友燕處,意有 所行輒去,人疑其多嗔。與人期,雨雪虎狼不避也。上元初,更隱苕溪,自稱桑薴翁,闔門著書。或獨行野中,誦詩擊木,裴回不得意,或慟哭而歸,故時謂今接輿 也。久之,詔拜羽太子文學,徙太常寺太祝,不就職。貞元末,卒。

羽嗜茶,著經三篇,言茶之原、之法、之具尤備,天下益知飲茶矣。時鬻茶者,至陶羽形置煬突間,祀為茶神。有常伯熊者,因羽論複廣著茶之功。御史大夫 李季卿宣慰江南,次臨淮,知伯熊善煮茶,召之,伯熊執器前,季卿為再舉杯。至江南,又有薦羽者,召之,羽衣野服,挈具而入,季卿不為禮,羽愧之,更著《毀 茶論》。其後尚茶成風,時回紇入朝,始驅馬市茶。

Xin Wenfang (active circa 1304-1324 C.E.)

Biographies of the Talents of the Tang Dynasty, 1304 C.E.

Chapter three

Lu Yü

Yü, his sobriquet was Hongjian; parentage unknown. Early in life, the Zen master Zhiji discovered the foundling on a riverbank and raised him as his disciple. When he was grown, he was ashamed to take the tonsure, and so using the Book of Changes, he divined the hexagram jian 漸 from the hexagram jian 蹇 which read: “Hong jianyü lu, qi yü keyong wei yi, The wild goose gradually draws near land, its feathers can be used for rites” and began using the characters for his surname and given name.

He was learned, and there was nothing in which he did not excel. By nature, he was witty. When he was young, he hid among theater actors and composed Mocking Banter of a myriad jokes. During the Tianbao reign period, the local bureau appointed him master of entertainments, but he later went into seclusion. In antiquity, people called this “to cleanse oneself of a humble past.” At the beginning of the Shangyüan reign period, he built a hut along Tiaoxi Stream, closing his door to read books and talking and gathering with eminent monks and lofty scholars all day long. In appearance, he was ugly; he stuttered but was eloquent. Hearing people do good, he felt good. Regarding friends, although obstructed by tigers and wolves, he would not desert them.

He called himself Old Man Mulberry and also Master of East Ridge. He was skilled in ancient tunes, songs, and poems, the epitome of elegance. He authored a great many books. He went back and forth by skiff among the mountain temples wearing only a gauze kerchief and straw sandles, a coarse cloth shirt and shorts. He knocked about the forest, dabbling in flowing streams, wandering in the wilderness, reciting ancient poems, unwilling to leave until dark. Filled with grief, he wailed and wept, and finally returned home. At the time, he was compared to Jieyü. He and the Buddhist priest Jiaoran shared a close rapport. He received an official post by imperial decree as Imperial Instructor of the Heir Apparent.

Lu Yü was fond of tea. He created a profound and subtle way and wrote the Book of Tea in three volumes which described the origins, methods, and equipage of tea. In time, he was known as the Immortal of Tea, and All under Heaven benefited from drinking tea. The tea guilds commissioned a ceramic figure of Yü and offered libations to it as a deity. When someone bought ten tea implements from a shop, he got a Hongjian figure.

Early on, the Censor-in-Chief Li Jiqing conducted an imperial tour of inspection in Jiangnan. Liking tea, he knew of Yü, and so he summoned him. Yü, in rustic clothes, entered ahead of his equipage. Li said, “Master Lu excells at tea; All under Heaven knows this. The water from Zhongling on the Yangzi is also exceptional. Now these two marvels have come together in a rare moment of providence. You, honored recluse, must not miss this opportunity.” When the tea was over, Li ordered a servant to give money to Lu Yü. Humiliated, Lu Yü blamed Li Jiqing, and in revenge wrote The Ruination of Tea.

He was a worthy traveling companion of Huangfu Zai. Once, the minister Bao Fang was in Yüe, and Yü went to serve him. Huangfu Zai composed a preface for him, saying “Gentleman Yü studies the philosophies of both Confucius and Buddha, and esteems song and poetry. Be it boating to a distant cottage or a lonely island, he is compelled to roam. Whether weir fishing or angling from a jetty, he goes where he wishes. Yüe is a strategic land of mountains and waters and therefore bears a heavy badge of office. Lord Bao appreciates and admires Master Yü; he shows him the utmost respect. It is a rare treat to taste the fish of Jinghu, much like grasping the reflection of the moon in a stream.” Composed for the Book of Tea to spread its fame.

辛文房

唐才子傳

卷三

陸羽

羽,字鴻漸,不知所生。初,竟陵禪師智積得嬰兒於水濱,育為弟子。及長,恥従削發,以《易》自筮,得《蹇》之《漸》曰:『鴻漸於陸,其羽可用為儀。』始為 姓名。有學,愧一事不盡其妙。性詼諧,少年匿優人中,撰《談笑》萬言。天寶間,署羽伶師,後遁去。古人謂『潔其行而穢其跡『者也。上元初,結廬苕溪上,閉 門讀書。名僧高士,談宴終日。貌寢,口吃而辯。聞人善,若在己。與人期,雖阻虎狼不避也。自稱『桑薴翁』,又號『東崗子』。工古調歌詩,興極閑雅。著書甚 多。扁舟往來山寺,唯紗巾藤鞋,短褐犢鼻,擊林木,弄流水。或行曠野中,誦古詩,裴回至月黑,興盡慟哭而返。當時以比接輿也。與皎然上人為忘言之交。有詔 拜太子文學。羽嗜茶,造妙理,著《茶經》三卷,言茶之原、之法、之具,時號『茶仙』,天下益知飲茶矣。鬻茶家以瓷陶羽形,祀為神,買十茶器,得一鴻漸。 初,禦史大夫李季卿宣慰江南,喜茶,知羽,召之。羽野服絜具而入,李曰:『陸君善茶,天下所知。揚子中泠水,又殊絕。今二妙千載一遇,山人不可輕失也。』 茶畢,命奴子與錢。羽愧之,更著《毀茶論》。與皇甫補闕善。時鮑尚書防在越,羽往依焉,冉送以序曰:『君子究孔、釋之名理,窮歌詩之麗則。遠野孤島,通舟 必行;魚梁鉤磯,隨意而往。夫越地稱山水之鄉,轅門當節鉞之重。鮑侯知子愛子者,將解衣推食,豈徒嘗鏡水之魚,宿耶溪之月而已。』集並《茶經》今傳.

Tianmen County Annals of the Qianlong Reign Period

Chapter Seventeen

Recluses

Lu Yü, courtesy name Hongjian. Lu was upright and resolute, innately profound. Although a solitary man, there was never a day when he neglected to be trustworthy and dutiful. Indeed, his Autobiography reveals this was so. Yü described himself as intelligent and inquisitive, industrious in his focus and zeal. His resolve was absolute and endless, and he conducted himself with determination and conviction. Somber by nature, he was, however, easy-going in the company of others. He had the love of learning of Shen Zhilian, the obsession of Ruan Dongping, the tenacity and authority of Zhuang Qiyüan, and the destructive passion of Wang Changshi. Is this not worthy and virtuous? Is this not the manner of the lofty and detached? When he was raised in the Zen of Master Ji, the foremost Perfection was revealed as ending the cycle of birth and death – Nirvana. But how is this not comparable to following the footsteps of Zhi Daolin? Thus, his adherence to the Confucian canon was unwavering, and though he endured humiliation and servitude, he was unrepentant. He attended the academy on Fire Gate Mountain, built a thatched cottage on the banks of Reed Stream, and was a reclusive, independent man of ease. In the dusty world, he was once an actor and a master of entertainments, and he met celebrated high officials like Li Qiwu, Cui Guofu, and Zou Fuzi who befriended him throughout his life. Ultimately, he was summoned to court as Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent, a post that he declined. Have his works been transmitted correctly? They are most certainly preeminent and exceptional. The Book of Tang recorded that “Three days after his birth, geese came to protect him. As an adult, he cast a divination and received the character ‘gradually’ from the hexagram ‘to proceed in stages’ from which he derived his surname Lu.” In his Autobiography of the Imperial Instructor, he states, “Indeed, it is not known where he is from.” After a hundred years or more, there was then Xiyi Chen Tuan, a rare man of antiquity who received a surname. Fate is often inexplicable. A bibliography of Lu Yü’s writings are in the classics, records, and annals, and his autobiography is found in numerous compendia.

乾隆《天門縣志》

卷十七

隱逸 陸羽

陸羽字鴻漸,性介而情深,雖獨行未嘗一日忘忠孝也。觀其“自序”盡之矣。羽自言慧而通,其用功專而銳,其立志窮而不變,其為人果於自信,勇於為人而慵於周旋。有沈織廉之好學,阮東平之興致,庄漆園之解粘釋縛,王長史之終為情死。是殆庶乎?狂狷者流耶!當其養於積公之禪,名蘭勝果以証無生,何遽不若支道林之躅?乃執儒典不屈,至淪辱厮養不悔。負書火門,結廬苕溪,自位於放人佚士,同塵於伶人樂師,一時名流達官如李齊物、崔國輔、鄒夫子諸人,皆握手如平生。終以文學征於朝不赴。遺文垂后其亦矯乎?克自振拔者矣。《唐書》謂其“生三日而雁銜以來。及長,佔於‘蹇’之‘漸’而得姓名。”即“文學自傳”亦曰:“不知何許人也”。后百余年有希夷摶冒陳,得姓蓋古之異人,常有不可解於造物如斯者。所著書目在經籍志,自傳在余編。

Source

Qialong Tianmen xianzhi 乾隆天門縣志 (Tianmen County Annals of the Qianlong Reign Period, 1767; reprint Jiangsu guji chuban she江蘇古籍出版社, 1922), Zhang Biao章鑣 (js 1742, died 1768) and Zhang Xüecheng章學誠 (js 1778, 1738-1801), ch. 17.

An Anthology of Poetry and Biographical Sketches from Hubei

Chapter Twenty-eight

Tianmen

Lu Yü, courtesy name Hongjian. Yü, a man of the Kaiyüan reign period. He was awarded the offices of Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent and Great Invocator of the Court of Imperial Sacrifices, which he declined. He was upright and resolute, innately profound. Although a solitary man, there was never a day when he neglected to be trustworthy and dutiful. Indeed, his Autobiography reveals this was so. Yü described himself as intelligent and inquisitive, industrious in his focus and zeal. His resolve was absolute and endless, and he conducted himself with determination and conviction. Somber by nature, he was, however, easy-going in the company of others. He had the love of learning of Shen Zhilian, the obsession of Ruan Dongping, the tenacity and authority of Zhuang Qiyüan, and the destructive passion of Wang Changshi. Is this not worthy and virtuous? Is this not the manner of the lofty and detached? When he was raised in the Zen of Master Ji, the foremost Perfection was revealed as ending the cycle of birth and death – Nirvana. But how is this not comparable to following the footsteps of Zhi Daolin? Thus, his adherence to the Confucian canon was unwavering, and though he endured humiliation and servitude, he was unrepentant. He attended the academy on Fire Gate Mountain, built a thatched cottage on the banks of Reed Stream, and was a reclusive, independent man of ease. In the dusty world, he was once an actor and a master of entertainments, and he met celebrated high officials like Li Qiwu, Cui Guofu, and Zou Fuzi who befriended him throughout his life. Ultimately, he was summoned to court as Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent, a post that he declined. Have his works been transmitted correctly? They are most certainly preeminent and exceptional. The Book of Tang recorded that “Three days after his birth, geese came to protect him. As an adult, he cast a divination and received the character ‘gradually’ from the hexagram ‘to proceed in stages’ from which he derived his surname Lu.” In his Autobiography of the Imperial Instructor, he states, “Indeed, it is not known where he is from.” After a hundred years or more, there was then Xiyi Chen Tuan, a rare man of antiquity who received a surname. Fate is often inexplicable. A bibliography of Lu Yü’s writings are in the classics, records, and annals, and his autobiography is found in numerous compendia.

Yü wrote his Autobiography of the Imperial Instructor Lu for which the source is the New History of the Tang Dynasty by Song Zijing. According to Stories of Cause and Consequence by Zhao Lin, “Master Ji, a monk surnamed Lu from the Hidden Dragon Monastery at Jingling, found a baby boy on an embankment and raised him. Accordingly, the monk gave his last name Lu to the child.” The boy was intelligent and gifted, but at first Master Ji did not allow him to study the Confucian classics and found a hundred ways to humiliate him. But in the end, Yü was insistent and eventually went to Fire Gate Mountain to study with the academician Master Zou, and in time he became close friends with the poet monk Jiaoran. Yü’s scholarly vision was erudite and untrammeled. Witty and lighthearted, unbound by convention, he was an exemplary man of East Asia. His writings include The Bonds between Ruler and Subject, Unraveling Origins, Genealogy of Four Surnames South of the Yangzi River, A Record of Famous People from North and South, A Record of Successive Officials in Wuxing, The Interpretation of Dreams, and the Book of Tea which is his only extant work. He wrote the poem entitled Song and the verse “I have only a thousand longings, ten thousand yearnings for the western waters of the River.” In his hometown, there is Overturned Cauldron Island and the Spring of Master Lu, places for the serving and connoisseurship of tea. Yü wandered about Jianghu, the riverine south. During the An Lushan Rebellion on the Central Plains, he wrote Four Lamentations; and during the invasion of the JiangHuai region by Liu Zhan, he composed the ode, The Obscuring of Heaven.

The Imperial Instructor Lu wrote poems of linked verse with Yan Zhenqing, Wu Yün, Li E, Yang Ping, Geng Wei, Huangfu Ceng, Liu Qüanbai, and the monk Jiaoran. Though the poems are not wholly complete, the collection expresses the zenith of the age. The poem Climbing Mount Yan to View Stone Vessel Rock contains the lines, “Idle steps drawn by the deep pines, the kudzu tender and fragile to the touch.” From Singing to the Wind at the Water Pavilion, “Shaking the flagstaff, the cicada stridently shrieks, parting the curtain, all worries disappear.” From Seven Character Verse, “The gentleman, masters, and recluses of the Han all followed the teachings of Confucius of Lu, a mild yearning in admiration and in vain, how regretful the mispoken words.” From the untrammeled lines of “Opening the Border Lands, “In the old forests of the border lands, strange rocks lay scattered about” and “Deep valleys possess perilous streams and tumbled cliffs.” Accounts of the Sea and Splintered Events contains the dramatically powerful couplet from Inscription on the Spring at Kangwang Valley, “Swiftly flowing from a thousand high rocks, chasing the boat from Jiujiang.” From the especially fine literary style of Seven-Character Verse written on East Mountain at Kuaiji, “Moon-colored, the cold tide enters Shan Stream, the cries of the black apes break west of the Green Woods. The ancients followed its eastward flow, the river weed floats year after year through the emptiness.” From the poem West River in Notes on Jingling Poetry, “I do not covet wine vessels of yellow gold nor covet cups of white jade. I do not long for court matins nor long for evening audiences. I have only a thousand longings, ten thousand yearnings for the western waters of the River.” And from Sipping Tea on a Moonlit Night, “Drifting blossoms invite the traveler to drink and talk, to stay a while longer.”

湖北詩征傳略

卷二十八

天門

陸羽字鴻漸

羽,開元時人。詔授太子文學,徙太常寺太祝,不就。性介而情深,雖獨行未嘗一日忘忠孝也。觀其“自序”盡之矣。羽自言慧而通,其用功專而銳,其立志窮而不變,其為人果於自信,勇於為人而慵於周旋。有沈織廉之好學,阮東平之興致,庄漆園之解粘釋縛,王長史之終為情死。是殆庶乎?狂狷者流邪耶!乃執儒典不屈,至淪辱厮養不悔。負書火門,結廬苕溪,自位於放人佚士,同塵於伶人樂師,一時名流達官如李齊物、崔國輔、鄒夫子諸人,皆握手如平生。終以文學征於朝不赴。遺文垂后其亦矯乎?克自振拔者矣。《唐書》謂其“生三日而雁銜以來。及長,佔於‘蹇’之‘漸’而得姓名。”即《文學自傳》亦雲“不知何許人也”。后百余年有希夷摶冒陳為姓,蓋古之異人常有不可解,於造物若斯者。

羽嘗自撰《陸文學傳》,宋子京《唐書》本之。趙隣《因話錄》:“竟陵龍蓋寺僧積公陸某,於堤上得一初生兒,育之。遂從其姓”。穎悟多能,積公初不令習儒,百方挫辱而終不懈。遂至火門山從鄒夫子學。旋與皎然為莫逆交。學瞻詞逸,詼諧縱橫,東方曼倩之籌也。其遺文如《君臣契》、《源解》、《江西四姓譜》、《南北人物志》、《吳興歷官記》、《佔夢書》,《茶經》,唯《茶經》行世。嘗作《歌》雲:‘千羨萬羨西江水,獨向竟陵城下來。’”“故有覆釜洲陸子泉,皆烹茶品茶處。羽放跡江湖,當安祿山亂中原,為《四悲詩》﹔劉展窺江淮,作《天之未明賦》。

陸文學嘗與顏真卿、吳筠、李萼、楊憑、耿湋、皇甫曾、劉全白、釋皎然諸公,為聯句詩不盡可傳,然亦可匯紀以志一時之盛。《登峴山觀石尊》雲:“鬆深引閑步,葛弱供險捫。”《水亭詠風》雲:“動枓蟬爭噪, 開簾客罷愁。”《七言》雲:“漢朝舊學君公隱,魯國今從弟子科。隻自傾心慚濡煦,何曾將口恨蹉跎。”《辟疆園》逸句雲:“辟疆舊林間,怪石紛相向。”又雲:“絕壑方險尋,亂崖亦危造。”出《海錄碎事》,其《題康王谷》有“瀉從千仞石,寄逐九江船”一聯,殊有筆力。又有七絕雲:“月色寒潮入剡溪, 青猿叫斷綠林西。昔人已逐東流去,空見年年江草齊。”則在會稽東小山作也。神韻尤佳。《竟陵詩話》《西江》雲:“不羨黃金罍,不羨白玉杯,不羨朝入朝,不羨暮登台,千羨萬羨西江水,獨向竟陵城下來。”《月夜啜茗》雲:“泛花邀過客,代飲引清言。”

Source

Hubei shi zheng zhuanlüe 湖北詩征傳略 (An Anthology of Poetry and Biographical Sketches from Hubei, 1881), Ding Suzhang 丁宿章 (active 1875-1908), comp. (Xiaogan: Dingshi Jingbei caotang chuban丁氏涇北草堂出版, 1881), ch. 28.