Miscellaneous Rhymes on Tea

Pi Rixiu of the Tang dynasty

Miscellaneous Rhymes on Tea

Tea Garden

At leisure, seeking Mount Yaoshi.

Finding and entering the tranquil garden.

Cultivating tea and creating the estate,

Planting tea and planning the field.

Water trickles from the stone spring,

Clouds thread the break in the cliff.

Summer just starting,

White flowers brimming with misty rain.

Teaists

Born on Mount Guzhu,

Now old among the stony gardens.

We talk only of tea,

Our robes scented with mists and clouds.

The courtyard hidden by the jade green plants;

We remain, despite the threat of wild beasts.

At day’s end, laughing as we return home,

Baskets lightly tied about our waists.

Tea Shoots

Budding, three to five inches;

Growing and fostered by the cliffs.

Dreading the cold, shoots turn red;

Doubting the warmth, buds turn purple.

Round like a polished jade axle,

Fragile like a frozen jade flower.

Each encounter is sparse;

Even the sunny side of the mountain is draped in a distant dream.

Tea Basket

Taking up the bamboo basket at dawn,

Crossing quickly to the tea grove.

Steadily tossing in the russet buds,

Our backs soaked with dew.

We rest near Cloud Spring;

Returning, the basket still hangs in the misty tree.

How rewarding is this life,

Even precious gold is eclipsed.

Tea Hut

Sunlit cliffs cradle the commons;

Voices, playful and lively.

The shed draws water from Red Spring;

Before firing, steam the russet buds.

Husbands pulp the tea, next

Wives mold tea, then rest.

Close the brushwood gate;

Pure fragrance fills the moonlit hills.

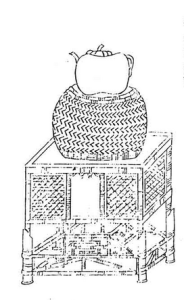

Tea Stove

Within the mountains, tea happening:

The stove set in the foothills;

The water boils, the rocks emit steam;

The tinder fired, the pine sap fragrant.

Jade leaves steamed, then gelled;

Green essence heated to a luster.

Wherefore such bitter hardship?

One by one, the creation of unsurpassed fare.

Tea Hearth

Chiselled beneath the Green Cliffs,

Precisely two feet deep.

Plastered simply to the rocks,

Fire does not obstruct the stony veins.

It begins the parching of the golden cakes,

Gradually drying the jade tea.

Fir Woods encompasses nine li,

Facing the mountain side.

Tea Brazier

The town of Longshu has fine artisans

Casting this beautiful form.

Standing compact and solid,

Boiling with a rushing sound.

Shadowed by evening clouds — the hermitage;

Luminated by melting snow — the window of pines.

Now ladling rich tea;

Lore and legend grasp this exceeding purity.

Tea Bowl

The artisans of Xing and Yue

All create bowls

As round as the moon,

As light as the clouds.

The floral froth enthralls the eye,

Fruit fragrant foam cleanses the mouth.

A single glance from beneath the pines;

Master Zhi knew this…

Brewing Tea

Fragrant spring water — like milk,

Boil to form strings of pearls.

When crab eyes spray,

Suddenly fish scales rise.

The sound of rain in the pines;

The foam creates a misty green.

Rain still drips in the mountain…

Wine need not be drunk for a thousand days.

唐 皮日休

茶中雜詠

茶塢

閑尋堯氏山

遂入深深塢

種荈已成園

栽葭寧計畝

石窪泉似掬

岩罅雲如縷

好是夏初時

白花滿煙雨

茶人

生於顧渚山

老在漫石塢

語氣為茶荈

衣香是煙霧

庭從𣟤子遮

果任獳師虜

日晚相笑歸

腰間佩輕簍

茶筍

褎然三五寸

生必依岩洞

寒恐結紅鉛

暖疑銷紫汞

圓如玉軸光

脆似瓊英凍

每為遇之疏

南山掛幽夢

茶籝

筤篣曉攜去

驀個山桑塢

開時送紫茗

負處沾清露

歇把傍雲泉

歸將掛煙樹

滿此是生涯

黃金何足數

茶舍

陽崖枕白屋

幾口嬉嬉活

棚上汲紅泉

焙前蒸紫蕨

乃翁研茗後

中婦拍茶歇

相向掩柴扉

清香滿山月

茶竈

南山茶事動

竈起岩根傍

水煮石發氣

薪然杉脂香

青瓊蒸後凝

綠髓炊來光

如何重辛苦

一一輸膏粱

茶焙

鑿彼碧岩下

恰應深二尺

泥易帶雲根

燒難礙石脈

初能燥金餅

漸見幹瓊液

九裏共杉林

相望在山側

茶鼎

龍舒有良匠

鑄此佳樣成

立作菌蠢勢

煎為潺湲聲

草堂暮雲陰

松窗殘雪明

此時勺複茗

野語知逾清

茶甌

邢客與越人

皆能造茲器

圓似月魂墮

輕如雲魄起

棗花勢旋眼

蘋沫香沾齒

松下時一看

支公亦如此

煮茶

香泉一合乳

煎作連珠沸

時看蟹目濺

乍見魚鱗起

聲疑松帶雨

餑恐生煙翠

尚把瀝中山

必無千日醉

Source

Pi Rixiu 皮日休 (834-883 A.D.), “Chazhong zayong 茶中雜詠 (Miscellaneous Poems on Tea) in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Quan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 611, nos. 47-56.

Notes

The ten poems by Pi Rixiu were responded to by his friend Lu Guimeng陸龜蒙 (?-881), “Fenghe Ximei chaju shiyong 奉和襲美茶具十詠 (Offering Matching Rhymes to Pi Rixiu’s Ten Songs on Tea).” For a translation of the responding themes and poems by Lu Guimeng, see

The Huzhou Lei Tea Jar

An ancient jar is the earliest object identified with certainty as tea ware. The ceramic was found in a third century tomb where it was offered as funerary goods, that is to say, objects of daily use placed in the burial chamber as sacrifice to the dead. The size, shape, and features of the pottery reveal that it functioned as a storage container, while its inscription verifies that the jar was once designed to hold tea.

Made of glazed stoneware, the vessel is of fair size and well-proportioned. Generally globular in shape, the body narrows from a broad waist to a flat foot and bears a stamped geometric design known as leiwen or thunder pattern. The mouth opens from a short neck, a rounded ring that surmounts a shoulder marked by a double string band and four small lugs. The glaze is a mottled greenish brown color and covers the vessel evenly from the neck to a few broad lappets below the waist.

Under the glaze on the upper shoulder – in the space between the neck ring and the string décor – the jar bears an inscription: the character cha 茶 or tea incised neatly in clerical script. Created with a pointed stylus, the character is a combination of four straight and angled lines and four dots, a simplified rendering in eight strokes of the nine-stroke character cha 茶, meaning tea.

The jar was excavated on April 19, 1990 by the Huzhou Museum from an old tomb discovered at Luojiabang Village, Biannan Township, a site two miles southwest of Mount Wen and just west of Huzhou, Zhejiang. The unoccupied burial chamber was built of brick in the manner of the late Han dynasty and contained other well-made ceramic wares, most notably an animal-shaped ewer, a bird-headed tripod vessel, and a four-lugged jar. The styles of the architecture and the pottery indicate an age spanning from the end of the Eastern Han (25-220) to the Three Kingdoms period (220-280), circa third century of the Common Era.

Described as the archaic vessel type known as lei 罍, the jar measures 33.7 centimeters high and 36.3 centimeters wide with diameters of the mouth and base at 15.5 and 15.5 centimeters, respectively. According to speculation, the ceramic was made at the early pottery kilns of Deqing located about thirty-five miles south of Huzhou. Alternatively and more likely, the jar was manufactured at the ancient Yue kilns near present Ningbo. Both kilns made early green wares known as celadon.

The lei vessel was fully developed as a lidless storage container in both ceramic and bronze during the Shang dynasty, circa 13th-12th centuries B.C., and remained basically unchanged for millennia to this day. To close, the jar was fitted with a wooden plug, sealed with bamboo sheath and fine thick paper, and by use of the lugs was bound with cord. When sealed, the jar was resistant to air and damp. Aesthetically appealing, technically superb, uniform in shape, lightweight, and capacious, the lei was not only the stock storage container of the ages but also perfect for keeping tea.

For several reasons, the Huzhou lei is important to the art and tradition of tea. Dated to the third century, the jar is the earliest known ware expressly dedicated to tea by its manufacture and inscription. The lei is further evidence of tea in the Han and proof of the early epigraphic development and use of cha 茶 to represent the tea plant and its produce, the character recognizable even in a highly stylized and abbreviated form. Both the celadon jar and the tea it was intended to store were likely made near Huzhou, a region that formerly was known as Wucheng. Thus, the celebrated affinity of tea for celadon may be traced from at least the late Han and the Three Kingdoms period. According to the Record of Wuxing by Shan Qianzhi (died ca. 454), the marquisate of Wucheng produced a tribute tea from the imperial estates on Mount Wen in the third century, precisely contemporaneous with the Huzhou lei.

Figures

Lei Jar, 3rd century

China: Eastern Han dynasty-Three Kingdoms period

Ceramic: stoneware with applied glaze

Four lugs, stamped décor, inscribed cha 茶

H: 33.7 cm. W: 36.3 cm.; diameter: mouth 15.5 cm.; base 15.5 cm.

Huzhou Museum

Excavated from the brick tomb M1:1 at Luojiabang Village, Biannan Township, Huzhou, Zhejiang, April 19, 1990. See Zhang Bo 張柏, Zhongguo chutu ciqi quangji 中國出土瓷器全集 (Collected Ceramic Wares Excavated in China) (Beijing: Kexue chuban she, 2008), p. 26.

Tea and the Materia Medica of Tao Hongjing

Tao Hongjing of the Liang dynasty

Baiying and Kucai

Baiying 白英, white flower. Its taste is sweet, its medicinal character is cold, and it is not poisonous. It cures chills and fever, the eight jaundices, indigestion and thirst, restores equilibrium and benefits qi 氣, the life force. Prolonged use lightens the body and extends life. One name for it is gucai 谷菜, herb of the valley; another name is baicao 白草, white herb. It is produced in the mountains and valleys of Yizhou. In spring season, pick the leaves; in summer, pick the stems; in autumn, pick the flowers, and in winter, pick the roots. The various prescriptions do not prescribe it, for it is only a food staple cooked in water for people to drink. It only grows in mountains and valleys…there is also baicao 白草, white herb, the leaves make soup to drink to relieve fatigue; however, the roots and flowers are not used. Only Yizhou has kucai 苦菜, a beverage drunk by the natives that promotes health and prevents disease. This is undoubtedly the case.

梁 陶弘景

本草經集注

卷第三

白英

味甘寒無毒

主治寒熱八疸消渴補中益氣

久服輕身延年

一名谷菜一名白草

生益州山谷

春采葉夏采莖秋采花冬采根

諸方藥不用

此乃有菜生水中人蒸食之

此乃生山谷…

又有白草葉作羹飲甚治勞而不用根花

益州乃有苦菜土人專食之皆充健無病疑或是此

Herb category of medicinals

Fruit, herbs, rice, and grains: nominal drugs of no practical application

Kucai 苦菜, bitter herb tea

Superior grade

Its taste is bitter, its medicinal character is cold, and it is not poisonous. It cures the five visceral organs and diseases, relieves gastric obstructions caused by eating grain, alleviates indigestion, intestinal distress, thirst, fever, and ulcers of the skin. Prolonged use calms the heart, benefits qi 氣 – the life force – quickens perception, lessens sleep, lightens the body, delays old age, dispels cold and hunger, and stays the decline of talent and the sublime nature. One name is tuku 荼苦; one, is xuan 選; and another, is youdong 遊冬. It grows in the mountains and valleys of Yizhou. It grows in the mountains and hills and along the roads. It lives through winter and does not die. It is picked on the third day of the third lunar month and dried in the shade. This herb is likely what is now known as ming 茗. One name for ming 茗 is tu 荼. It causes sleeplessness. It too does not wither in winter and is doubtless the same as that which grows in Yizhou. Only Yizhou has kucai 苦菜, which as stated is bitter. This herb kucai 苦菜 is already commented on in the entry of the herb baiying 白英, white flower, in the superior category of the first volume. It is written in the Record of Medicines by Master Tong that “the leaves of kucai 苦菜 grow lush in the third lunar month; in the sixth lunar month, flowers follow the growth of leaves; the stems are straight and the flowers, yellow; in the eighth lunar month, the seeds blacken; when the seeds fall, the roots extend their growth; in winter, the plant does not dry up. The present herb ming 茗 truly resembles this herb kucai 苦菜. The ming 茗 teas of Xiyang and Wuchang are comparable to those of Lujiang and Jinxi: they are all excellent. Easterners make only green ming 茗 tea. Ming 茗 tea is always beneficial. Of all beverages, ming 茗 tea compares with the edible leaves of various trees, asparagus sprouts, and china root: all are beneficial, bountiful, and valuable for their cooling properties. Badong has zhentu 真荼 tea, the leaves of which when fired twist and knot; these are made into a drink that causes sleeplessness. Zhentu 真荼 is undoubtedly similar to all these very teas. Now, the brewing of beautiful leaves to make tu 荼 tea compares with the herbal made of large black plums and its cooling effects. Nanfang has gualu mu 瓜蘆木, the wild tea tree, which is similar to ming 茗 tea in bitterness and astringency; the leaves are taken and crumpled into bits, brewed, and the liquor drunk. In consequence, there is sleeplessness all night long; indeed, for wakefulness the salt workers depend only on this drink. Along the breadth of all relationships, tea is of the utmost importance; first serve when guests arrive and add fragrant herbs.”

梁 陶弘景

本草經集注

卷第七

果菜米穀有名無實

菜部藥物

苦菜

上品

味苦寒無毒

主治五臟邪氣厭穀胃痹腸渴熱中疾惡瘡。

久服安心,益氣,聰察,少臥,輕身,耐老,耐饑寒,高氣不老

一名荼苦一名選一名遊冬

生益州川谷生山陵道傍淩冬不死

三月三日采,陰乾。疑此則是今茗

茗一名荼又令人不眠亦淩冬不凋而嫌其只生益州

益州乃有苦菜正是苦爾

上卷上品白英下已注之

《桐君藥錄》雲苦菜葉三月生扶疏六月花從葉出莖直花黃八月實黑實落根複生冬不枯

今茗極似此西陽武昌及盧江晉熙茗皆好東人只作青茗

茗皆有之宜人

凡所飲物有茗及木葉天門冬苗並菝皆益人余物並冷利

又巴東間別有真荼火燔作卷結為飲亦令人不眠恐或者此

世中多煮檀葉及大皂李作荼飲並冷

又南方有瓜蘆木亦似茗至苦澀

取其葉作屑煮飲汁即通夜不眠

煮鹽人唯資此飲爾交廣最所重客來先設乃加以香輩爾

Source

Tao Hongjing 陶弘景 (456-536), comp., “Baiying 白英” and “Kucai 苦菜),” Bencao jing jizhu 本草經集注 (Collected Commentaries to the Materia Medica), juan 3 and 7.

Figure

Artist unknown

Portrait of Tao Hongjing as a Daoist, detail

Yuan dynasty, 14th century

Album leaf: ink and color on paper

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Inscription for the Gentleman of Principle

Sheng Yong of the Ming dynasty

Inscription for the Gentleman of Principle

Shaped like the vault of Heaven and the square of Earth:

Bamboo sheathed metal, bamboo wrapped clay.

Within, a lively fire burns,

Bearing sounds of waves on the river Xiang.

One drop of sweet dew

Cleanses my poetic core.

A pure wind sweeps beneath my sleeves,

Carrying me beyond the realm and into the Void.

明 盛颙

苦節君銘

肖形天地

匪冶匪陶

心存活火

聲帶湘濤

一滴甘露

滌我詩腸

清風兩腋

洞然八荒

Source

Sheng Yong 盛颙 (1418-1492), “Kujie jun ming 苦節君銘 (Inscription for the Gentleman of Principle, 1478)” from Qian Chunnian 錢椿年 (active ca. 1530-1535) and Gu Yuanqing 顧元慶 (1487–1565), Chapu 茶譜 (Treatise on Tea, 1541) in Zhongguo lidai chashu huibian jiaozhu ben 中國歷代茶書匯編校注本 (Annotated Compilation of Tea Books of Dynastic China), Zheng Peikai 鄭培凱 and Zhu Zizhen 朱自振 (1934–present), comps. (Hong Kong: Commercial Press, 2014), p. 181.

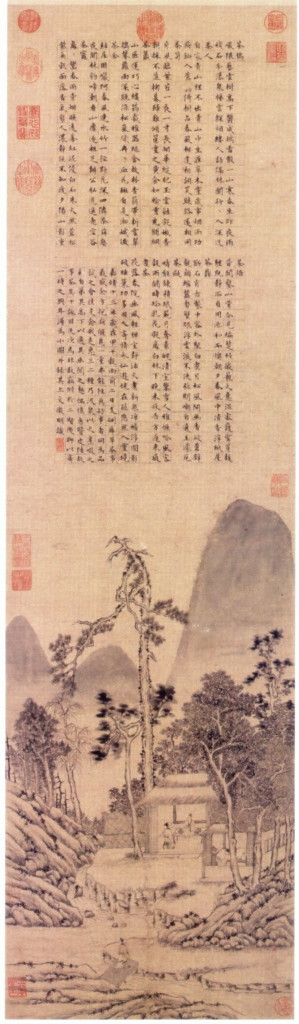

Three Encomia on the Ten Perfections of Tea

Wen Zhengming of the Ming dynasty

Three Encomia on the Ten Perfections of Tea

Tea Sprouts

The east wind blows across the russet tea,

In a single night it grows an inch.

A floral mist splits the heavy jade leaves,

Clouds gently congeal their tender fragrance.

The morning harvest fills less than a hand,

Returning in the evening, scolded for upsetting the tea basket.

The leaves, precious as yellow gold;

Transport the proffered tribute before the spring festival.

Brewing

Spring flowers fall, hiding the courtyard,

A gentle wind calms the meditation room.

Tend the fire to boil fresh spring water.

The cold moon floats round and shadowy.

Sleepless, yet ever writing of the worthy,

Faithful to the eternal emotions.

Wandering immortals flit about the brazier,

Effortlessly entering the spirit realm.

Stove

Everywhere nourished by spring rains,

Dark mists conceal distant peaks.

Tea contests Heaven’s ambrosia,

Crimson fire and green pine in harmony.

Purple essence condenses,

Descending among us, fragrant and rich.

Feeling tranquil and refreshed,

Sunset shadows the mountains.

Source

Wen Zhengming 文徵明 (1470-1559), “Chashi tu 茶事圖 (The Art of Tea, 1534),” Shiqu baoji xubian 石渠寶笈續編 (Sequel to the Treasure Coffers of the Stone Moat, 1793), Wang Jie 王杰 (1725–1805) et al., comps. (Taipei: Guoli Gugong bowu yuan, 1971), vol. 2, pp. 1051–1052.

Figure

Wen Zhengming 文徵明 1470–1559)

Chashi tu 茶事圖 (Art of Tea, 1534)

Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Song of Coveting Tea

Wu Kuan of the Ming dynasty

Song of Coveting Tea

I, Elder of the Brew, love tea as I love wine,

Three pints or fifty – there’s no counting.

Beginning in the tea room, there are no unnecessary things:

Just a tea stove and a tea pounder.

Here, there is nothing ever to do but brew tea.

All day long, the tea cup never leaves my lips.

Assisting today’s gathering, a single tea server;

Coming through the door, my guest, a true tea friend.

To express thanks for tea, emulate the poem of Lu Tong;

To brew tea, follow the ode of Huang Jiu.

The Sequel to the Book of Tea, I lend to no one.

The Addenda to the Tea Register, I let slip from the hand:

I will have nothing to do with planting mundane tea.

I know only the few acres of tea garden below this mountain.

Some people merely dream of roaming the tea country,

But I, right here and now, simply do nothing else.

明 吳寬

愛茶歌

湯翁愛茶如愛酒

不數三升幷五斗

先春堂開無長物

只將茶竈連茶臼

堂中無事長煑茶

終日茶杯不離口

當筵侍立惟茶童

入門來謁惟茶友

謝茶有詩學盧仝

煎茶有賦擬黃九

茶經續編不借人

茶譜補遺將脫手

平生種茶不辦租

山下茶園知㡬畞

世人可向茶郷游

此中亦有無何有

Source

Wu Kuan 吳寬 (1435-1504), “Aicha ge 愛茶歌 (Song of Coveting Tea),” Paoweng jia cangji 匏翁家藏集 (Collection of the Paoweng Family Treasures), (Shanghai: Hanfen lou Collection), book 2, juan 4, pp. 7b-8a in Sibu congkan chubian 四部叢刊初編 (Collection of the Four Categories, First Series), Zhang Yuanji 張元濟 (1867-1959), comp. (Shanghai, 1919), vols. 1557-1568.

A Place for Tea

Li Rihua of the Ming dynasty

A Place for Tea

A clean room – with just a broad couch, a ready table, burning incense, a cup of tea – empty of unnecessary things. While sitting in meditation, a pure ethereal force gathers naturally within me. As this chaste and numinous power grows, the foul and turbid effluvium of the world also shifts within and is steadily purged.

明 李日華

潔一室橫榻陳几其中爐香茗甌蕭然不雜他物但獨坐凝想自然有清靈之氣來集我身清靈之氣集則世界惡濁之氣亦徙此中漸漸消去

Source

Li Rihua 李日華 (1565-1635), Liuyan zhai sanbi 六研齋三筆 (Copious Notes from the Studio of Six Pursuits), juan 4, pp. 5b-6a, especially 6a in “Zajia lei 雜家類 (Miscellaneous Treatises),” “Zibu 子部 (Masters and Philosophers),” Qinding Siku quanshu 欽定四庫全書 (Complete Collection of the Four Libraries by Imperial Commission), compiled by Ji Yun 紀昀 (1724–1805) et al. (Beijing: Forbidden City, 1798).

Song of Tasting Tea at West Mountain Temple

Liu Yuxi of the Tang dynasty

Song of Tasting Tea at West Mountain Temple

Beyond the temple eaves, the mountain monks have many tea plants.

Spring arrives and the glow of the bamboo draws out new buds.

Like welcoming a guest, rise and smooth the robes to

Pick from all the lush growth the eagle beaks.

In a instant, the firing fills the room with fragrance.

For an elegant service, ply water from Jinsha,

Listen for the sound of rain and pines from the brazier.

White clouds fill the bowl, billowing here now there.

Even from afar, one whiff dispels the drunken night,

Cares are banished clean to the bone.

From sunny cliffs to shady ridges, each has a special quality,

But those cannot compare to this, moss-grown beneath the bamboo.

Yandi sampled flora but knew not this brew;

Tongjun was prescient yet knew not this flavor.

New buds are curled, not even half ever open.

From picking to brewing takes but a moment or so.

The aroma is like the scent of dew-soaked magnolia;

Next to the color of waves, the jade herb is peerless.

The monks say that the beautiful flavor is crucial to reclusion.

Pick, pick the rich, mellow leaves for the honored guest:

Don’t send it home.

Forget the brick well and bronze brazier,

For how can the spring leaves of even Mengshan and Guzhu

Ever survive the rigors of travel?

He who desires to know the pure, refreshing flavor of tea

Must be a man of sleeping clouds and creeping stones.

唐 劉禹錫

西山蘭若試茶歌

山僧後檐茶數叢

春來映竹抽新茸

宛然爲客振衣起

自傍芳叢摘鷹觜

斯須炒成滿室香

便酌砌下金沙水

驟雨鬆聲入鼎來

白雲滿盌花徘徊

悠揚噴鼻宿酲散

清峭徹骨煩襟開

陽崖陰嶺各殊氣

未若竹下莓苔地

炎帝雖嘗未解煎

桐君有籙那知味

新芽連拳半未舒

自摘至煎俄頃餘

木蘭霑露香微似

瑤草臨波色不如

僧言靈味宜幽寂

採採翹英爲嘉客

不辭緘封寄郡齋

甎井銅爐損標格

何況蒙山顧渚春

白泥赤印走風塵

欲知花乳清泠味

須是眠雲跂石人

Source

Liu Yuxi 劉禹錫 (772-842), “Xishan lanre shicha ge 西山蘭若試茶歌 (Song of Tasting Tea at West Mountain Temple, ca. 805) in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Qüan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), juan 356, no. 15.

Comment

First noted by Liu Yuxi circa 805, West Mountain Temple Tea was yet another example of loose leaf produced by a Buddhist monastery during the Tang dynasty. Half a century before, the poet Li Bo famously named Immortal Palm Tea, a loose leaf produced around 752 at the Jade Spring Temple in Jingzhou, modern Danyang, Hubei. The tea at West Mountain Temple was further noteworthy because it was grown amidst bamboo. Moreover, it was the special practice of the monks to serve guests tea that was not only from the monastery’s own garden but also picked, fired, and brewed especially for the occasion.

Liu Yuxi was a high official and a government reformist during the late Tang dynasty. At court, the reformists were opposed by supporters of the crown prince and by palace eunuchs. When the emperor died and the heir apparent ascended the throne in 805, the reformists were demoted and banished to provincial posts. As one of eight noted reformists, Liu Yuxi was sent into exile to become military adjutant at Langzhou, modern Changde, Hunan, where he spent ten years before being recalled to the capital in 815.

While in Langzhou, Liu Yuxi spent time at West Mountain Temple, a Buddhst monastery. The monks greeted visitors with a very special loose leaf tea. Planted in gardens behind the temple, tea was grown among moss and bamboo. When guests arrived, tea was picked from the bushes and immediately brought to the hall to be fired and brewed with Jinsha Spring water right in front of the visitors. The brew was so fresh that Liu Yuxi opined that not even Yandi the Fire Emperor (Shennong the Divine Cultivator) nor the Yellow Emperor’s physician Tongjun had ever tasted such a wonderful tea. He discouraged guests from sending the tea home, for it would suffer from the journey. Indeed, not even the rare teas of Mount Meng in Sichuan and of Huzhou in Zhejiang might survive the trip. Moreover, water and brewing method would not be the same as at the monastery. Liu Yuxi concluded that only a recluse residing at West Mountain Temple could know the true taste of tea.

Miscellaneous Poem

Wang Wei of the Liu Song dynasty

Miscellaneous Poems, number one of two

Alone and desolate, I close the high chambers,

Silent and empty, the grand halls.

Waiting for my lord who will not return,

I catch myself and go at once to tea.

王微

王微

雜詩二首 其一

寂寂掩高閣

寥寥空廣廈

待君竟不歸

收领今就檟

Source

Wang Wei 王微 (415-453), “Zashi 雜詩 (Miscellaneous Poem),” Chajing 茶經 (Book of Tea, 780 A.D.), Lu Yü 陸羽 (trad. 733-804 A.D.), comp. (Baichuan xüehai 百川學海, ed., 1273 A.D.), juan 3, part 7, p. 7b.

Figure

Gu Kaizhi 顧愷之 (ca. 345-406), attributed

Nüshi zhentu 女史箴圖 (The Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies), detail

Handscroll: ink and colors on silk

The British Museum

London

New Imperial Tribute Tea from Huzhou

Zhang Wengui of the Tang

New Imperial Tribute Tea from Huzhou, ca. 841

On a spring outing, returning tipsy by phoenix carriage,

Her coiffed peony blossoms teasing bobbled ornaments.

Fording the inlet, the faerie belle peeps through the screen

To announce the arrival of russet buds from Wuxing.

唐 張文規

唐 張文規

湖州貢焙新茶

鳳輦尋春半醉回

僊娥進水御簾開

牡丹花笑金鈿動

傳奏吳興紫筍來

Source

Zhang Wengui (active 830–853), “Huzhou gongbei xincha 湖州貢焙新茶 (New Imperial Tribute Tea from Huzhou, ca. 841) in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Qüan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 366, no. 11.

Figure

Zhou Fang (ca. 730-800)

Court Ladies Wearing Flowered Headdresses, 8th century

Handscroll: ink and color on silk

Liaoning Provincial Museum

The Ten Virtues of Tea

Liu Zhenliang of the Tang dynasty

The Ten Virtues of Tea

Take tea to dispel melancholy, banish sleep, increase vitality, expel disease, initiate decorum and humanity, express respect, cultivate sophistication, nurture the body, harmonize with the Dao, and regulate desire.

唐 劉貞亮

茶十德

以茶散鬱氣

以茶驅睡氣

以茶養生氣

以茶驅病氣

以茶樹禮仁

以茶表敬意

以茶嘗滋味

以茶養身體

以茶可行道

以茶可雅志

Source unknown

Liu Zhenliang 劉貞亮 (a.k.a. Liu Zhende 劉貞德 and Jü Wenzhen 俱文珍, active 787-813), imperial eunuch and respected supervisory commander of the Xüanwu Army 宣武監軍 at Kaifeng; rewarded by the emperor with the posthumous title Commander Unequalled in Honor 開府儀同三司.

Stories About Lu Yü

Feng Yan (active ca. 755-794 A.D.)

Record of Things Heard and Seen

Chapter 6

“Drinking Tea”

In the Discourse on Tea, Lu Hongjian of Chu explained the merits and methods of brewing and toasting of tea, devising twenty-four tea implements and using an elegant case in which to store them. Near and far, everyone imitated him, and every proper household kept a case of tea implements. Because of his teachings and embellishments, Lu Hongjian, as well as Zhang Boxiong, created a great movement in the art of tea. Princes and nobles and courtiers without exception all drank tea. Li Jiqing, the Censor in Chief, was sent to inspect the Jiangnan region and arrived at the district offices of Huai County. He was told that Zhang Boxiong excelled at tea, whereupon Lord Li summoned Zhang to attend him. Boxiong was dressed in a yellow, sleeveless gown and a black, silk cap, carrying in his own hands his tea utensils. He spoke with authority on the names of tea, showing discernment and giving instruction, expounding on the changes in methods. When the tea was brewed, Li sipped only two cups. Arriving in the Jiangnan region, Li was told that Lu Hongjian was skilled at tea, whereupon Lord Li summoned Hongjian to attend him. Hongjian wore rustic robes and entered accompanying his tea implements. After sitting, he earnestly gave instruction just as Boxiong had done. But in his heart, Li despised him. When the tea was over, Li ordered a servant to take thirty coins to pay “Doctor Tea Cook.” Having traveled widely throughout the south, Hongjian was intimately familiar with fame and celebrity, but this was a shameful incident to which he reacted by writing the Discourse on the Ruination of Tea.

封演

飲茶

封氏聞見記

卷六

楚人陸鴻漸為《茶論》,說茶之功效並煎茶炙茶之法,造茶具二十四事,以都統籠貯之。遠遠傾慕,好事者家藏一副。有常伯熊者,又因鴻漸之論廣潤色之。於是茶道大行,王公朝士無不飲者。御史大夫李季卿宣慰江南,至臨懷縣館,或言伯熊善茶者,李公請為之。伯熊著黃衫、戴烏紗帽,手執茶器,口通茶名,區分指點,左右刮目。茶熟,李公為歠兩杯而止。既到江外,又言鴻漸能茶者,李公復請為之。鴻漸身衣野服,隨茶具而入。既坐,教攤如伯熊故事。李公心鄙之,茶畢,命奴子取錢三十文酬煎茶博士。鴻漸游江介,通狎勝流,及此羞愧,復著《毀茶論》。

Yan Zhenqing (709-785 A.D.)

“Inscription on the Stele along the Spirit Path of the Honorable Master Li, Grand Master of the Palace with Gold Seal and Purple Ribbon, Acting Grand Mentor of the Heir Apparent, Concurrent Chamberlain for the Imperial Clan, Chief Minister, Minister of Works, Supreme Pillar of State, and Dynasty-founding Duke of Longxi County,” excerpt

Complete Literary Works of the Tang Dynasty

Chapter 342

His Eminence Li Qiwu was demoted to Prefect of Jingling Prefecture. At the time, Lu Yü Hongjian accompanied the Master on a tour of inspection of the region. Lu Yü stated that Li Qiwu stepped from his carriage and summoned his officers, saying to them: ‘Among officials, there are those who do not cultivate the sacred rites; among Buddhists and Daoists, there are those who are incompetent at monastic discipline; and among the common people, there are those who are reckless and impulsive. Before my taking office, none were held responsible. But from now onward, offenders will be relentlessly pursued.’ Within a number of years, the state of the prefecture completely changed, and Jingling flourished and prospered as in the golden age of the ancient sage emperor Fuxi.

顏真卿

金紫光祿大夫守太子太傅兼宗正卿贈司空上柱國隴西郡開國公李公神道碑銘

全唐文

卷三白四十二

公遂貶竟陵郡太守。時陸羽鴻漸隨師郡中,說公下車召人吏告之曰:“官吏有簠簋不修者,僧道有戒律不精者,百姓有泛架蹶馳者,未至之前,一無所問,而今而后,義不相容。”數年間一境丕變,熙然若羲皇之代矣。

Li Zhao (flourished circa 818-821 C.E.)

Supplement to the Dynastic History of the Tang, 827 A.D.

Chapter 3

In the Jiangnan region, there was a station master who did things his own way. When the governing prefect arrived on an official tour of inspection, the station master simply said, “The station is all in order. Please make your review.” Thereupon, the prefect proceeded. He first saw a room with the sign “Wine Storage” where various drafts were brewed. On the outside of the room was painted the image of a deity. The prefect asked, “What is this?” To which the station master answered, “That is Du Kang, the Sage of Wine.” The prefect then said, “Everywhere this is so.” At another room, the sign read “Tea Storage,” where tea was stored, and again there was an image of a deity. “What is that?” “That is Lu Hongjian, the Sage of Tea.” The prefect thought it was excellent and approved. At another room, the sign read “Pickle Storage,” where pickles were prepared. Again, there was a deity. “What is this?” The official said, “Cai Bojie.” The prefect laughed out loud, saying: “No need to display this!”

李肇

唐國史補

卷下

江南有驛吏,以干事自任。典郡者初至,吏白曰:“驛中已理,請一閱之。”刺史乃往,初見一室,署雲“酒庫”,諸醞畢熟,其外畫一神。刺史問:“何也?”答曰:“杜康。”刺史曰:“公有余也。”又一室,署雲“茶庫”,諸茗畢貯,復有一神。問曰:“何?”曰:“陸鴻漸也。”刺史益善之。又一室署云「葅庫」,諸葅畢備,亦有一神。問曰:“何?”吏曰;“蔡伯喈。”刺史大笑曰:“不必置此。”

Zhou Yüan (active ca. 773-816 A.D.)

“Composing Three Expressions of Being Moved after Visiting West Pagoda as Metropolitan Governor of Jingling”

Complete Literary Works of the Tang Dynasty

Chapter 620

The writings of the ancients included banners and funerary palls, songs of the meritorious, the heterodoxy and apocrypha, and works cherishing the past: flags of praise were posthumously bestowed; songs of the worthy were genuine expressions of form; the unorthodox were simply eccentric and unconventional; reverence for the bygone revealed true human feeling. In contrast, casting inscriptions in bronze and carving them in stone aggrieve the spirits. These are not respectful but rather quite maudlin. And what of my writings, do they revere the past? Objectively speaking, what are they to be taken as?

I, Zhou Yüan, who having written “His Honor Ma Zong of Fufen and his Military Commission over the One Hundred Ethnic Minorities,” formerly worked with the Honorable Li Fu of Longxi, Governor of Nanhai. Li Fu was ordered to move to Huatai. When Ma joined me on Li’s staff, it was in Lingnan at Rongzhou and Guangzhou for about seven meteoric years. Now, Ma Zong’s meritorious contributions fill the world, his literary compositions fly forth from his brush, and as Military Commissioner of Nanhai, he is mother and father to its people. By comparison, I, Zhou Yüan, as a mere provincial governor, just look frail and weak. But, we two are enveloped with one another like “twin carp,” each of us harboring deep regard for the regions of Chu and Yüe. Li Fu, however, lived but a short life and died young. This indeed is the first expression of being so moved and stirred!

Li Fu’s father was the late Li Qiwu, who was a man of great virtue and Governor of Jingling. Because he was born during his father’s days as governor, Li Fu was given the name Fu. Alas! I, Zhou Yüan, who carelessly and disgracefully administers Li Qiwu’s province, was on Li Fu’s staff, and I now govern his father’s prefectural realm. Alack! Li Qiwu! In the official residence, the songs and bells are now extinguished, and Li Qiwu has been buried these many years – now only tears and lamentations. This is indeed the second expression of being so moved and stirred.

For many unbroken years, the Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent Lu Yü and I were aides together in Li Fu’s office. Lu Yü was truly my brother! In his Autobiography, Lu wrote he was from Jingling. At the time, he said, “Jingling is beautiful. There is no place better than my hometown.” Now, I administer his town of Jingling. Remembering his words, Lu Yü truly did not exaggerate. Ma Zong also knew Lu Yü. Speaking on his behalf, Ma addressed Lu Yü’s background. Lacking records in the ancestral shrine, Lu Yü began life as a foundling, and until he came of age at nineteen, he lived the life of a Buddhist monk, received Buddhist teachings and its Law, and esteemed the Buddha. A saint, indeed!

Lu Yü, sobriquet Hongjian, a serious scholar of the One Hundred Schools and a companion to half the dignitaries and senior officials under Heaven. He was, moreover, a straightforward and honest critic, a practitioner of witty repartee – a lofty and sublime recluse whose literary works and integrity are incomparable. Ah!

In the west of my prefectural seat, there is Fufu, a place that is round like a mountain top and in the middle of which is a monastery and a pagoda. The bamboo there – as big around as an arm – is a dark green thicket, indeed a living portrait of Hongjian’s teacher. My, such sadness! Resembling a mountain peak, the bamboo of Chu surrounds the pagoda. The abbot whose remains are buried within the pagoda is the same monk who raised and nurtured Lu Yü. The cane in front of the pagoda is the same bamboo once planted and cultivated by Lu Yü.

I look upon the pagoda, the earthly memorial to the elder monk. The bamboo grows old and weathered, and Lu Yü is long gone. As a governor of Chu, I come to Fufu and its Buddhist cloister. It is daylight, and there is no incense burning for Lu Yü. All is abandoned, scattered and lost. My robes tremble in the Chu wind. This is indeed the third expression of being so moved and stirred.

Written in verse, seven characters per line. If Li Fu could read the Three Expressions of Being Moved, how could he hold back his tears and not be sad? Delivered below the pagoda, this composition is Zhou Yüan’s crowning achievement.

周願

牧守竟陵因游西塔著三感說

全唐文

卷六百二十

古人之文,有旌物而為者,歌功而為者,詭時而為者,感舊而為者:旌物,謚也﹔歌功,形也﹔詭時,詐也﹔感舊,情也。若乃折裂金石,騷牢鬼神,莫尚乎感也。予所作者,其感舊耶?客曰:何謂也?

願與百越節度使扶風馬公,曩時俱為南海連率隴西李公復從事 。公詔移滑台,扶風公洎予又為幕下賓,從容兩地,七改星火。今扶風公勛庸滿世,文翰飛走,續鎮南海,(11)作民父母﹔而願才貌單薄,亦為刺史。繇是二客雙鯉 ,殷勤於楚越。隴西短齡閱川而物故,予感一也。

隴西先人諱齊物,彼大德嘗為竟陵郡守。公生於守之日,故名復。嗚呼!願以散拙忝公先人之州,往為子寮,今刺父郡。悲夫!隴西也。歌鍾燼滅於池館,九原極零乎薤露,其感二也。

願頻歲與太子文學陸羽同佐公之幕,兄呼之。羽自傳竟陵人,當時羽說“竟陵風土之美,無出吾國。”予今牧羽國,憶羽之言不誣矣。扶風公又悉於羽者也,代謂羽之出處:無宗祊之籍,始自赤子,洎乎冠歲,為竟陵苾蒭之所生活,老奉其教。如聲聞、辟支,以尊乎竺乾。聖人也!

羽,字鴻漸,百氏之典學鋪在手掌,天下賢士大夫半與之游。加以方口諤諤,坐能諧謔,世無奈何,文行如軻,所不至者,貴位而已矣。噫!我州之左,有覆釜之地,圓似頂狀,中立塔廟, 篁大如臂,碧籠遺影,蓋鴻漸之本師像也。悲歟!似頂之地,楚篁繞塔。塔中之僧,羽事之僧﹔塔前之竹,羽種之竹。視夫僧影泥破,竹枝筠老而羽亦終。予作楚牧,因來頂中道場,白日無羽香火,遐嘆零落,衣搖楚風,其感三也。是為三感說七言詩以語陳事。

扶風公覽三感之說,豈得不酸涕濕目,以著詞致於塔下,冠願鄙章之首邪

Li Fang (925-996 A.D.)

Extensive Records of the Taiping Era, 978 A.D.

Chapter 399

“Lu Hongjian”

In the spring of 814, Zhang Youxin, who had just become famous, arranged to gather with other National University Students of Grace at the Jianfu Temple. Youxin and Li Deyü arrived first and went to rest in the quarters of the monk Xüanjian along the west corridor of the monastery. Just then a monk from Chu arrived and set down a bag to rest. The bag contained several books. Youxin took out a volume and read through it. The writing was all notes and closely detailed. At the end were inscribed the words A Record of Water for Brewing (the word “record” was originally the word “places” according to the emendation of a Ming dynasty copy). In the time of Emperor Taizong [sic], Li Jiqing was governor of Huzhou. When he arrived at Weiyang, he met the recluse Hongjian. Li Jiqing had heard of Lu Yü and was pleased with the chance travel with him. When they arrived at the post station along the Yangzi, it was about dinner time. Li Jiqing said, “Master Lu excels at the art of tea. All under Heaven know this. The water at Nanling along the Yangzi is also exceptional. Today the chance meeting of these two marvelous things is one in a thousand. Why neglect this opportunity?” He ordered a trustworthy and diligent military officer to take a jar and a boat to the deepest part of the Nanling to fetch water. While waiting, Lu Yü cleaned his utensils. Very soon after, the water arrived. Lu Yü used a ladle to scoop out some, saying, “This is indeed river water, but it is not drawn from Nanling. It seems to be water taken from along the shore.” The officer replied, “I rowed the boat and entered the deepest part of the water. This was witnessed by several hundred people. How dare I deceive you?” Lu Yü said nothing, and then he poured from the jar half the water and quickly stopped. Again, he used a ladle to scoop out some and said, “Now this is water from Nanling.” Suddenly startled, the officer hastily knelt and said, “As I was holding the jar level from the Nanling to the riverbank, the boat swayed and the water spilled. Fearing the loss, I added water from the shore. The recluse’s discernment is divine insight, indeed! Who dares conceal or deceive him! Li Jiqing was amazed and filled with admiration. The several tens of bystanders were all shocked and alarmed. Since Lu Yü’s perception was so keen, Li then asked him if he would judge the merits and demerits of water from the places he experienced. Lu said, “The water of Chu is superior. The water of Jin is the most inferior.” Li Jiqing then arranged a sequence of water from places all ranked according to Lu Yü. (This was published as the Book of Water)

李昉

太平廣記

卷三百九十九

陸鴻漸

元和九年春,張又新始成名,與同恩生期於薦福寺。又新與李德裕先至,憩西廊僧玄鑒室。會才有楚僧至,置囊而息,囊有數編書。又新偶抽一通覽焉,文細密,皆雜記,卷末又題雲《煮水紀》(“記”原作“處”,據明抄本改)。太宗朝,李季卿刺湖州,至維揚,遇陸處士鴻漸。李素熟陸名,有傾蓋之歡,因赴郡。抵揚子驛中,將食,李曰:“ 陸 君善茶,蓋天下聞,揚子江南零水,又殊絕。今者二妙千載一遇,何曠之乎!”命軍士信謹者,挈瓶操舟,深詣南零取水,陸潔器以俟。俄水至,陸以杓揚水曰:“江則江矣,非南零者,似臨岸者。”使曰:“某棹舟深入,見者累百人,敢绐乎?”陸不言,既而傾諸盆,至半,陸遽止。又以杓揚之曰:“自此南零者矣。”使蹶然大駭,馳下曰:某自南零赍齊至岸,舟蕩半,懼其尠,挹岸水以增之。處士之鑒,神鑒也,其敢隱欺乎!”李大驚賞,從者數十輩,皆大驚愕。李因問陸,既如此,所經歷之處,水之優劣可判矣。陸曰:“楚水第一,晉水最下。”李因命口佔而次第之。(出《水經》